Quests to Thrive

College experiences among Black transgender, queer, bisexual, lesbian, gay, and/or same gender loving students

For many young people, attending a college or university is a key part of emerging adulthood, when the sense of who they are—as individuals, in relationships, and in their potential futures—begins to solidify. The choices they have, the opportunities they encounter, and the decisions they make are affected by social identities including gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, ability, age, and body size. For students whose identities include multiple othered categories, a higher education journey can be a boon, a burden, or both.

In my ongoing research on thriving, I have learned a lot about the college and university experiences of emerging adults who are Black and transgender, queer, bisexual, lesbian, gay, and/or same gender loving (TQBLG+/SGL). What I discuss in this article is largely gleaned from my 2014–18 “To Simply Be” study. In the study, I found that in some ways, attending a college or university contributed to the participants’ quests to thrive in their academic and personal lives and that in other ways, it undermined them. Some participants found that their ability to thrive at a campus changed over time. In all cases, the participants’ perspectives offered rich insights about what it’s like to attend a college or university while existing in bodies and with identities that are not expected to succeed there.

Scholars offer numerous frameworks and definitions for the concept of thriving. Many refer to it as resilience, acknowledging hardships and struggles but not always what is possible beyond bouncing back from difficulties. Social psychologists Virginia E. O’Leary and Jeannette R. Ickovics have described thriving as “more than a return to equilibrium.” Some scholars use psychologists Martin Seligman and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s framework of positive psychology, which seeks “to understand and build the factors that allow individuals, communities, and societies to flourish.” Still others portray thriving as self-actualization, which psychologist Abraham Maslow described as one’s “desire to become . . . everything that one is capable of becoming.” This is echoed in education researcher Bettina Love’s call to center Black queer youth efforts to create a world “where they [can] be whoever they [feel] they truly [are].”

Psychologist Carol D. Ryff and scientist Burton H. Singer describe psychological well-being as people’s ability to live “a life rich in purpose and meaning, continued growth, and quality ties to others.” Psychologist Charles S. Carver calls thriving “the better-off-afterward experience.” But for some populations, like the young people I have interviewed, significant stress is ongoing and cumulative: there is no “afterward experience.” While research on thriving, flourishing, and well-being is bountiful, little of it focuses intersectionally (in a way that is attentive to compounded oppression and discrimination) or developmentally on the thriving needs or experiences of Black TQBLG+/SGL emerging adults. There’s a fair amount of discourse on resilience, but not on what’s attainable in addition to it.

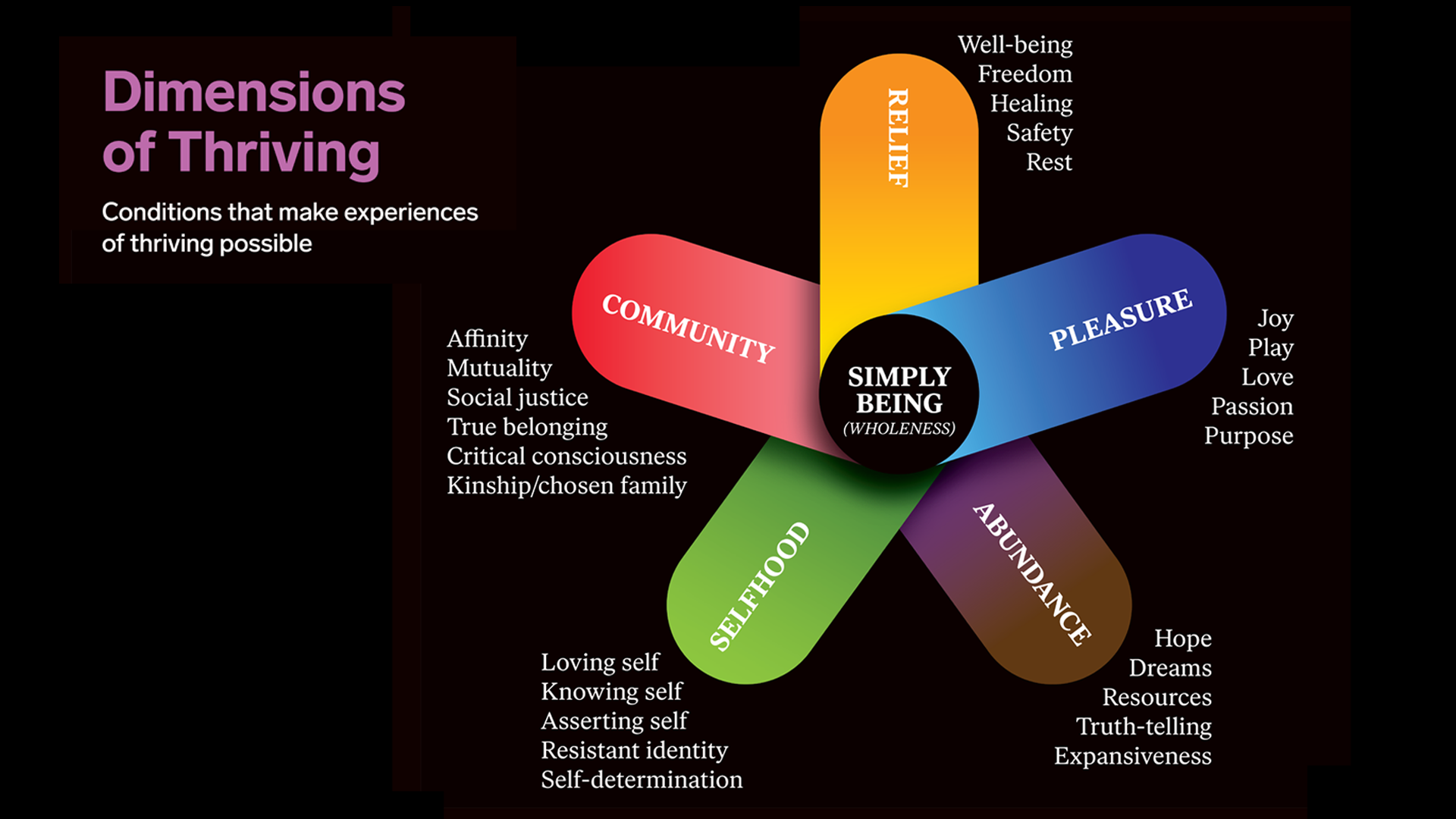

When I asked my study participants to describe what thriving might look like for them and what conditions would make it possible, they told stories that reveal the following six dimensions:

>> Community: as supportive, affirming affinity communities (particularly those made up of other Black or “of color” TQBLG+/SGL people), including chosen family (deep kinship developed outside biological or legal relationships).

>> Selfhood: as self-acceptance, self-awareness, self-actualization, and self-determination.

>> Abundance: as resources to take care of necessities and for “abundant” things like free time, travel, self-exploration, and independent housing.

>> Pleasure: as pleasurable activities, from spending time with close friends to sitting in the sunshine.

>> Relief: from stressors such as being stigmatized or bullied, worrying about a loved one, having insufficient funding, and even being unhoused.

>> Simply being: When all five of the other dimensions were present, participants’ stories were about being able to “simply be,” “just exist,” or “be whole.” This required a resistant identity, through which they claimed their inherent dignity and right to exist and be loved. The sense of “simply being” typically happened in the company of chosen family; in spaces that felt safe; with the availability of space, time, resources, and hope; and where the outer world’s stigmas and stressors were impotent and joy was present.

Each of my study participants listed a series of strategies and practices they used to achieve or reclaim thriving, from staying organized to meditating to making time for friends to prioritizing their musicianship. Although no one remained in a state of perpetual thriving, every participant described thriving experiences. Just being asked to consider the question of their thriving was a new and evocative experience that helped them reshape ideas about themselves and their futures.

Though the young people I spoke with often encountered more burdens than benefits on their higher education journeys, some elements of their experiences did align with dimensions of thriving. And, at times, campus-based resources made thriving possible.

One student, Dante (participant names have been changed), had struggled socially and academically the year before he studied abroad. In Brazil, though, he had space to take care of himself and to reflect, taking time to recuperate after difficult moments. He felt he could redefine himself and explore without a fear of failing. “Thriving means having your identity supported, your identity affirmed,” he said. “You are put in a situation where you can learn, fail, make mistakes, and still understand yourself as someone who will be capable of greatness and is worth greatness.”

He realized that he experienced many moments of thriving when he was near the ocean. It was a revelation he took with him, relocating to South America near the coast during his doctoral studies.

Another student, Forrest, also experienced a period of thriving related to campus-facilitated travel. The first instance was during an eighteen-day Canadian wilderness expedition for first-year students. The cost was prohibitively high, but Forrest received a scholarship. He later became an expedition leader, which subsidized his participation in subsequent trips. It was in being able to see himself as a leader for the first time that Forrest felt like he was thriving. “I was always that passive person,” he said. “Feeling that I had something of value and people could see in me greatness and that I could coach them and teach them wilderness skills and also engage in emotional intelligence and help do conflict resolution was really important to me.”

Forrest went on to lead a sustainability-themed house on campus for a year, hosting a variety of outdoor experiences. When the year ended, the outdoor program became a club. This, along with a study abroad trip to China, was a highlight of his higher education experience.

Another of my participants, Lara, felt able to “thrive more” when she enrolled in a Portuguese class in which she “learned about Brazil as a society and how Brazil functions and the racial tensions that exist there.” She was learning, she said, about something she loved while also learning about her own history.

Although she initially felt isolated on campus, “surrounded by these really straight White people who didn’t know how to be culturally sensitive or racially sensitive or just pretty much sensitive to human beings,” she eventually developed a support system, including “queer people of color friends” and found love and intimacy with her girlfriend, Gheera. They were able to date openly and live together, something that would have been punished back at home.

Living on campus, away from home, was also important for Marcus, who had been outed, made temporarily homeless, and subjected to an abusive stepfather during high school. Also crucial to Marcus’s thriving was distance from a mother who held conservative beliefs about gender and sexual orientation.

Another participant, Bruescht, attended a historically Black university where being in a Black community was like going home. “It just felt very familial when dealing with administration and staff,” he said. They “treated you like you were their child or their niece or nephew. I felt very safe on my campus, and I did feel very loved.”

Bruescht was able to study abroad twice by fundraising on campus. Attending the university, he felt, had made him more resourceful, autonomous, and confident. Nonetheless, he was rejected while rushing a fraternity because of his perceived sexual orientation. He also struggled to find a TQBLG+/SGL community, as he wasn’t ready to disclose that he was gay. Bruescht encountered both wonderful and terrible aspects of being at a university. He did not feel he thrived there.

Everett (they/them) attended three universities over the course of roughly eight years. A California State University student, Everett was among those whose higher education career was prolonged by course oversubscription and, as a result, amassed a sizable debt. But this journey, Everett reflected, showed them their capability and perseverance. Among the boons Everett described were opportunities to develop skills like project management, group leadership, and research. Because of well-taught courses and opportunities to visit interesting places, their sense of the world and its possibilities expanded.

Everett first attended two universities in San Francisco, living with family to save money and enjoying the city’s robust TQBLG+/SGL culture and community. At a third university, near Los Angeles, Everett developed a close-knit friend group but was geographically engulfed in a politically conservative White community both on and off campus. Students who could afford to live off campus found some relief from the restrictive culture, but Everett relied on subsidized on-campus housing. They often felt stuck and isolated, as the effort required to see friends off campus could be taxing.

When Everett and their friends sought to expand inclusivity and awareness on campus—through educational and supportive events, invited speakers, and tough conversations—they received pushback from peers, staff, and administrators. Everett’s friend group was often singled out and received disparate treatment. One especially destabilizing situation stands out. Everett and a handful of friends were employed as resident assistants, with responsibility for community building, resident safety, and education. They depended on these jobs as a source of stable affordable housing, as well as income. When the time came to renew employment contracts, multiple members of this group were targeted for termination. Parents and advocates got involved, and the campus launched an investigation that uncovered a pattern of mistreatment by senior staff. The inquiry found that although the students had been doing their jobs well, when they had called attention to exclusionary and discriminatory behavior, it made supervisors (and some peers) uncomfortable. Notably, Forrest had a similar experience at his campus in the northwest.

As important as it is for people to survive their encounters with oppression, it is also crucial to design beyond resilience for sustained and widespread thriving. Colleges and universities have tremendous potential to support Black TQBLG+/SGL students in not only experiencing but also planning for vibrant, flourishing lives. With particular attention to these students’ developmental needs as both emerging adults and complex individuals living in a deeply flawed society, educators can prioritize access, affordability, affinity communities, advising, adventuring, and the acquisition of critical skills. The young people who generously lent their voices to my research have offered abundant guidance for designing higher education experiences that are a boon rather than a burden. Are we courageous enough to follow their lead?

Illustration by Carl De Torres