Unbreaking News

What colleges and universities are doing to stem the local journalism crisis

Erica Perel knows firsthand what it’s like to be a local newsroom leader fighting to keep a publication alive.

After spending a decade as a daily news reporter, Perel worked as the general manager of the Daily Tar Heel, the independent student newspaper at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). As one of the paper’s nonstudent, full-time administrators, Perel was above the fray of the daily news coverage, focused instead on matters of revenue and circulation.

Partway through her tenure at the Tar Heel, Perel enrolled in the Table Stakes Newsroom Initiative, a yearlong media training program run by UNC’s Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media. The hands-on workshop helped Perel rethink the newspaper’s revenue model and the content needs of its readers. By the time she left the program, the Tar Heel had diversified from one revenue stream to four, setting the paper on a sustainable trajectory.

Perel’s own success story is one she now tells from the other side of the table, as director of the very same center at UNC. In that role, she now helps run Table Stakes, guiding other newsroom leaders—from journalists at small newspapers to those at public radio stations—through challenges like developing a digital audience or obtaining grants.

“It’s helping newsrooms understand how organizations change and how to create change in their organizations,” Perel says.

The Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media at UNC is one of many such programs at colleges and universities across the country that are leveraging the power, resources, and funding of higher education institutions to help stem a rapid decline in local news. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the number of newsroom employees nationally dropped by 57 percent between 2004 and 2020. During roughly the same period, the United States lost 1,800 newspapers, leaving nearly two hundred counties in the country without a single local paper, according to UNC’s Hussman School of Media and Journalism.

This crisis in journalism also portends a crisis of democracy. Studies show that communities without a local paper are less prosperous, with higher poverty rates and more government corruption. They’re also left without a shared set of facts, allowing political divides to deepen and flare up.

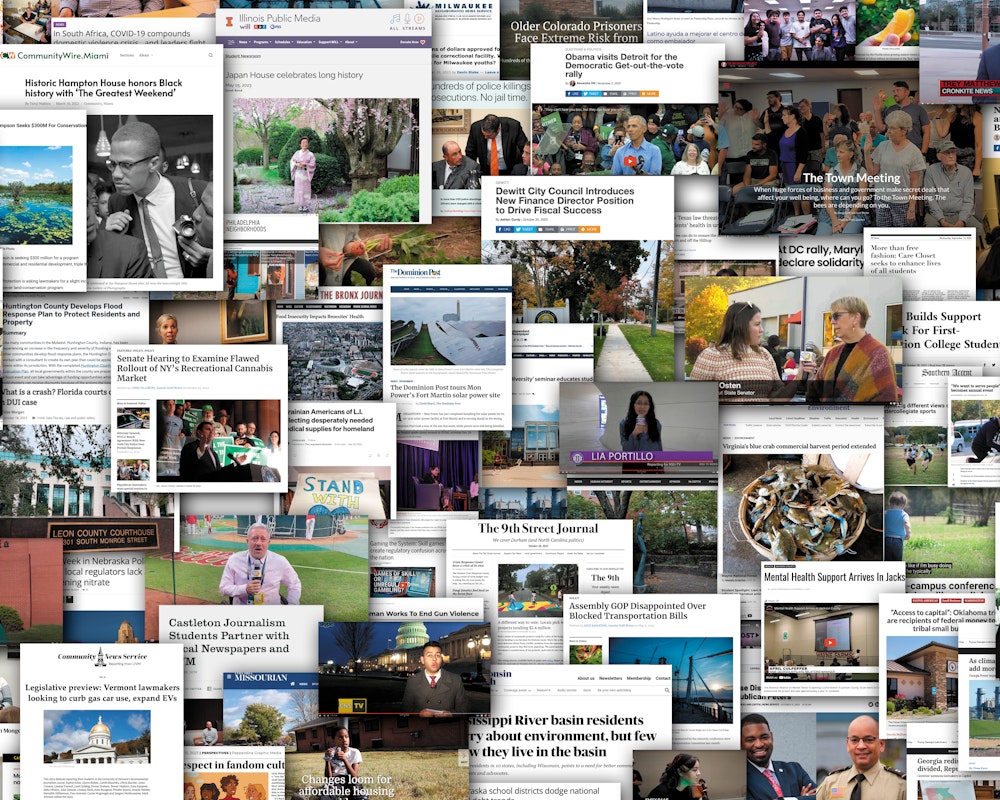

But a new wave of interest in local news promises to turn the tide. A growing set of programs at colleges and universities is lending resources, expertise, and sometimes even student-produced journalism to give local media outlets a leg up. It could still be years, even decades, before the efforts fully reverse the decline, but they’re undoubtedly boosting civic engagement and hands-on learning along the way.

“It’s really important to know that universities and journalism schools have a role to play in helping solve the local news crisis,” Perel says.

Much of Perel’s work at the Center for Innovation and Sustainability in Local Media involves bringing people together. “Our mission is to help create a better future for local news,” Perel says.

The center does that mostly through education and outreach to news organizations in the local community. The Table Stakes training is the flagship program, and every year it works with ten to twelve newsrooms from across the Southeast. The participants range from century-old newspapers like the Pilot in Moore County, North Carolina, to radio and TV outlets like West Virginia Public Broadcasting. Perel has seen many successful outcomes, with participating newsrooms learning to create digital subscription models, build more capacity, and do more with limited resources.

The center also conducts applied research, mapping the local information ecosystem—essentially creating a census of North Carolina’s news and information sources—and highlighting issues like burnout among journalists, which was the focus of one recent report. The survey found that 70 percent of local journalists experienced work-related burnout and that 72 percent had considered leaving their job. “The journalism workforce is a key component to [local news] sustainability in the future,” Perel says, noting that the report struck a nerve within the community. “You can’t be sustainable if your workforce is on the edge.”

The template for this kind of work—supporting local news through research centers at college and university journalism schools—has been replicated all over the country.

At Montclair State University in New Jersey, the Center for Cooperative Media was created as part of the School for Communication and Media, founded in 2012.

“We’re very externally facing,” says Stefanie Murray, the CCM’s director. “Our [center] is more of a vehicle for community engagement.”

The bulk of the center’s work involves training, professional development, coaching, and consulting for local news outlets in the state. “Anything and everything we can do to help people be successful,” Murray says.

Sometimes that is providing training on new tools or technology like Google Analytics or the latest Twitter alternative. Sometimes it’s offering a session on legal issues facing newspapers, like how to navigate open-records requests or deal with threats of a lawsuit. The training curriculum is different every year based on the results of a survey. “We really listen to what our constituents tell us,” Murray says.

The center also hosts a monthly press briefing, where local outlets—especially ethnic community newspapers—are invited to interview a prominent newsmaker or policy expert that they might not usually have easy access to, like the state comptroller. This was especially helpful during the early days of the pandemic, Murray says, when expert sources were crucial to public health coverage.

The center at Montclair does applied research, too, focused on ecosystem mapping and topics related to local news. One recent report dived into the state of ethnic and community media in New Jersey, and a research project helped “three nascent news and information outlets better understand the information needs of their communities.”

About forty-five minutes west of Chapel Hill, another university in North Carolina is testing out a model for supporting local news with the power of a large institution.

The North Carolina Local News Workshop sprang up in the summer of 2020, a time when all manner of crises were made visible by the pandemic—not least of which was the lack of reliable information sources in many small communities across the country. “It was launched to respond to the local news crisis specifically here in North Carolina,” says Shannan Bowen, the workshop’s executive director.

The idea for the workshop had been brewing among faculty at Elon University for the better part of a decade and eventually took shape as a regional initiative to improve access to local news.

“Journalism is fundamental to our mission,” says Kenn Gaither, dean of Elon’s School of Communications. Though the school has five distinct majors (journalism, strategic communications, cinema and television arts, communication design, and media analytics), “journalism is really what leads the way, and journalism is where we spend a lot of our time and resources,” Gaither says.

But the faculty of that journalism program felt the local news crisis was directly hurting enrollment and career prospects for their students.

“Anyone who’s in a school of journalism or communications will tell you that it’s a struggle,” Gaither says. “We are trying to combat that.”

Creating, housing, and partially funding the North Carolina Local News Workshop is one way that Elon is doing so. “What the workshop tries to do is bring together, almost like a magnet, some of these independent ideas and initiatives and get people around the table talking about collaborations,” Gaither says.

Indeed, the efforts of the workshop mirror what’s being done by the centers at UNC, Montclair, and elsewhere. The workshop hosts summits and statewide events around “shared challenges and solutions” for local news, such as the need for more newsroom employees and how to raise the funds to hire them. Bowen also uses her own network—and that of the university—to fill in gaps in local newsrooms.

‘It’s really important to know that universities have a role to play in helping solve the local news crisis.’

“The workshop itself is not a funder, but we provide capacity to other organizations in the form of connecting people with resources,” Bowen says. For example, if a news outlet needs to figure out an audience strategy, she might connect them to an expert in that field or personally coach them herself.

For the past couple of years, the workshop has also been focused on “community listening,” an effort to learn more about local news and information needs. “One thing that we’ve learned is that state government policy issues aren’t often understood by people across the state who are not in the state capitol,” Bowen says. These residents also don’t see the impact that state policies have on their lives. To solve this issue, Bowen is developing a program to help local newspapers deliver more state political news to their communities in a way that feels relevant to residents. Strategies include localizing statewide stories and decisions and using new formats to explain and contextualize this kind of news.

The other clear message Bowen has heard from newsrooms during her listening tour is that “everyone is struggling with capacity. People need more resources, more reporting, more tools and technology.” Here, Bowen again acts as a coach and connector, helping organizations apply for grants (which vary from project-based to general operating support, from a variety of different sources) or think through a new revenue model (such as digital subscriptions) or expand into a new community by establishing roots in a new part of the state.

Success for those local newsrooms translates to success for local communities. “People value trusted sources. They want timely information from those trusted sources,” Bowen says.

Gaither sees it in even broader terms: “We’re not just talking about journalism—we’re talking about communities and democracy.”

When Richard Watts, director of the Center for Research on Vermont and a senior lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Vermont (UVM), was helping his campus start a journalism program in 2019, he quickly decided he didn’t want to replicate the many outstanding journalism schools that already exist.

He decided, instead, to build the program in partnership with local media. “That old model of internships”—where legacy papers hire and mentor a select few students—“has collapsed, mostly,” Watts says. “And we wanted to give our students these applied experiences.”

The result is a journalism program in which students, working under the supervision of an editor who is a member of the university faculty, learn the skills of their trade by writing local news stories—and getting them published in local outlets.

Watts sees the model as one piece of the solution to the problems facing local media. “We have this absolute crisis in local news,” he said. And “we have tens of thousands of college students writing news stories who could be writing stories for local papers.”

Watts says the program at UVM is mutually beneficial: local newsrooms get an additional source of coverage—again, vetted by the university program’s editor—and students get some of their first published clips.

Aubrey Weaver, a junior at UVM, is a prime example. She’s a political science major and didn’t initially have ambitions in journalism. But she saw a poster on campus advertising Watts’ Community News Service and figured it would be a good way to learn more about local and state politics, so she signed up. “I just got hooked, and I’m learning a lot,” she says.

Weaver has since spent three semesters reporting and writing stories that are published in local Vermont media. For much of that time, she was at the statehouse, filing articles for papers that often don’t have the resources to employ a capitol correspondent. “It’s just a way that we can help each other,” says Weaver, who’s received a mix of college credits and financial stipends for the work.

After starting the news service, Watts soon realized that a number of other colleges and universities were also giving their students hands-on learning opportunities and wanted to help journalism schools with similar programs learn from each other, so he created the Center for Community News at UVM. “The CCN is a national center to document and encourage university-led student reporting programs,” he says.

Through surveys and research, Watts has identified 130 such programs in the United States. About 20 are statehouse reporting classes for which students act as correspondents covering state government for local papers.

Watts’ center leads monthly conversations on such topics as recruitment and fundraising and runs training sessions, like the University/Statehouse Reporting Conference, around the country. “It’s all about just trying to show [colleges and universities] what others are doing,” he said. “It’s about trying to be a clearinghouse, a central gathering point where people can learn from each other and grow more [student reporting programs].”

The center’s website also acts as a repository of case studies. At Franklin College, a team of three to seven students joins a veteran journalist every semester to report at the Indiana Statehouse, writing stories that often wouldn’t get covered otherwise. Students at the University of Georgia now run a 150-year-old weekly newspaper, the Oglethorpe Echo, which would have shuttered had it not been scooped up by a nonprofit partnering with the university. And at Louisiana State University (LSU), a journalism class allows students to investigate unsolved, racially motivated crimes from the past, under the guidance of a former New York Times reporter.

Allison Allsop, a senior political science and political communication major at LSU, got her start with the cold case project and soon gravitated toward the university’s statehouse reporting program. This summer, she filed stories for the Hammond Daily Star, a newspaper located east of her hometown of Baton Rouge. “Especially as a student who isn’t directly studying journalism, these programs have been monumental in my understanding of how journalism works,” she says, adding that it’s gratifying to support the local news ecosystem. “I really do think that it’s a very vital resource for publications across Louisiana. They really do rely on us.”

Much like Kenn Gaither, the Elon University dean, Watts sees value in these programs beyond a college or university classroom. Local news “gives people a shared understanding of what’s happening around them, and from that comes a greater level of trust in institutions and a higher likelihood to engage in their community, to vote,” he says. “Without local news, people turn to national, competing, ideological outlets. And that increases polarization. All these things are being laid at the doorstep of disappearing local news.”

Watts also believes this programming is valuable for students even if they don’t follow a journalism career path. “It’s training students to be citizens. Some will go on to be journalists, and some won’t,” he says. “We really hope that all the students will be more engaged citizens through learning how government works.”

The work of these many centers, from North Carolina to New Jersey, sound a lot like the types of projects usually undertaken by independent nonprofits. So why do so many of these programs live on college and university campuses?

“A lot of this work could absolutely be done by an organization that stands on its own,” says Stefanie Murray, director of the Center for Cooperative Media at Montclair State University. “But for us, being affiliated with a university, for a lot of folks it’s credibility and stability. . . . Universities are good conveners, they’re stable, and they have infrastructure.”

Colleges and universities are natural places to host the workshops and training sessions that many of these centers put on, and are often already trusted by local news outlets, Murray says. Plus, institutions are set up to receive grant funding, the kind of philanthropic support that keeps most of these centers afloat. And a college or university is an obvious home for the applied research that’s often part of the journalism centers’ missions.

The centers also play their part in supporting the goals of many higher education institutions. “Universities like Elon and others have missions to not only develop educational opportunities for students but to also impact communities through that education and work that they’re doing,” says Bowen of the North Carolina Local News Workshop.

Her work, she says, is not only enriching the education of students; it’s “helping North Carolinians get closer to local news and helping to reach a shared vision that we have, that everyone in North Carolina will have access to trustworthy news and information.”

Bowen also relies on the many resources that a university provides, without which her workshop would have a lot of additional expenses. “There’s a lot of benefits being based in the university system, while still having that autonomy to shape the strategy for the workshop,” she says.

‘We have tens of thousands of college students writing news stories who could be writing stories for local papers.’

Elon is just as happy to serve as the home for this kind of work. “It’s a partnership more than anything else, and that’s really what is critical to the workshop in general, is these partnerships,” Gaither says. “We want to continue to invest in it.”

The biggest challenge for this work, even with university support, is funding. Bowen’s and Murray’s workshops are primarily funded by grants, meaning the universities that host them are not picking up the whole tab of running the centers. Keeping them alive often comes down to fundraising.

Gaither sees a path to sustainable funding sources if these centers broaden their value proposition, going beyond simply supporting journalism to also supporting democracy.

“It really is an issue in the public good, and I think that’s a message we have to be focusing on nationally,” he says. “We need access to truthful, accurate news. If that dries up and goes away, the very fabric of our nation is at great risk.”