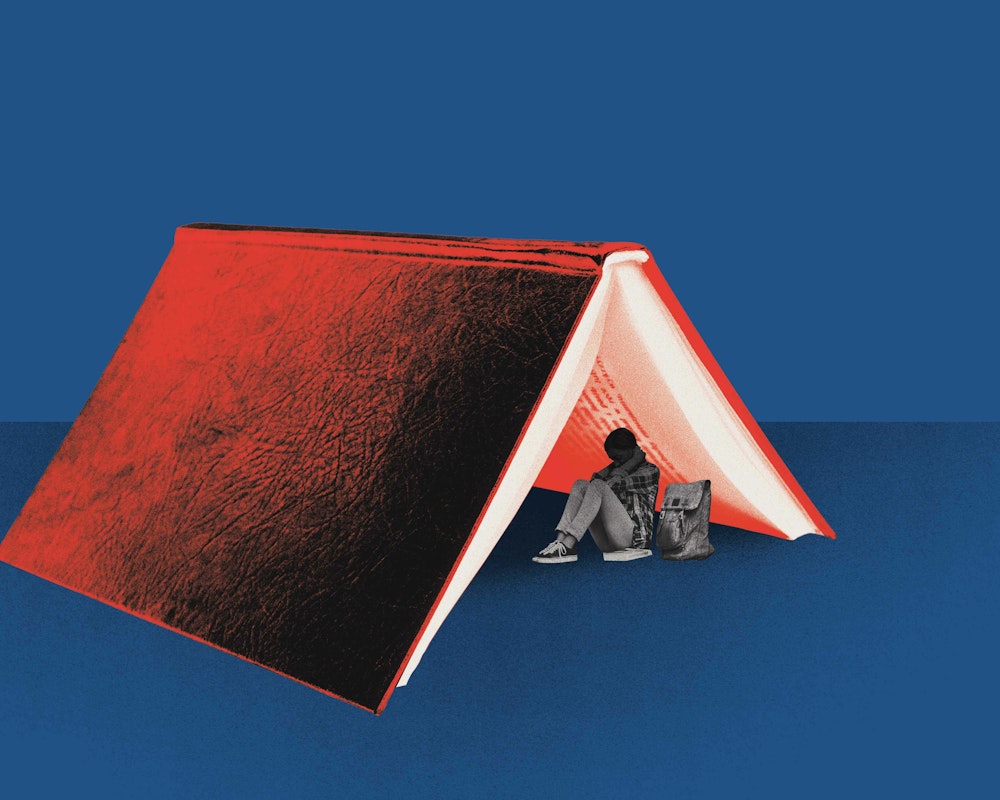

The Campus Housing Crisis

More and more students need a place to call home

When Maria (not her real name) began her freshman year at Brooklyn College in 2019, she wasn’t living in a dorm room. She was living in a homeless shelter.

Housing insecurity has been Maria’s difficult reality since she immigrated to New York City with her family in 2015. After arriving from Grenada, they moved into an overcrowded, one-bedroom apartment with her uncle and aunt, and by 2017, the family was drifting in and out of shelters. Maria became estranged from her mother in 2020, and after that, “I was on my own,” she says. She entered Covenant House New York, a city youth shelter, and juggled her studies, classes, and a weekend restaurant job with a constant search for housing.

“I was just so stressed,” says Maria, now twenty-one. “I could only live in Covenant House for thirty days, so my housing was very, very temporary. Not having a home was difficult because I had to constantly move.”

Maria then learned about the Neighborhood Coalition for Shelter (NCS), which assists New Yorkers who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. In October 2022, the organization created the NCS Scholars program to provide year-round stable housing and on-site support for City University of New York students. In its first year, the program served twenty-four students, including Maria, who now lives in a shared apartment in Long Island City and is set to graduate in May 2024 with a degree in business administration.

For students like Maria, housing challenges are becoming increasingly common. In a national survey published in 2021 by Temple University’s Hope Center for College, Community, and Justice, 43 percent of respondents at four-year colleges—and 52 percent at two-year colleges—said they had experienced housing insecurity during the previous year. Fourteen percent had been homeless. (Housing insecurity, according to HUD, includes problems such as high cost, poor quality and safety, and loss of housing.)

The problem is driven in part by basic economics: Scarce supply and increased enrollment mean more demand and higher prices. The COVID-19 pandemic is a factor as well. Some students saw their income drop, making them more vulnerable financially. Others craved a return to campus life after too many online classes, leading to increased competition for housing.

The price tags keep growing. The cost of tuition, fees, and room and board has risen by 32 percent at four-year institutions over the past two decades, according to an August 2023 report from the Bipartisan Policy Center (BPC). A 2023 investigation by Business Insider examined ten flagship state universities and found that “not accounting for inflation, the estimated cost of room and board rose by 25 percent—faster than the rise in tuition costs, which rose approximately 22 percent over the same time frame.” Many students are paying more for housing than for tuition. In the College Board’s 2022 Trends in College Pricing and Student Aid report, four-year students at in-state, public universities were budgeting an average of $27,940 for the 2022–23 academic year: $10,940 of those costs were for tuition and fees—and $12,310 were for room and board.

“We’ve all heard about tuition costs going up at universities across the country, but if you look under the hood, you’ll see that the room and board part of that calculation is skyrocketing,” says Francis Torres, a senior policy analyst with the BPC and co-author of the report on housing insecurity. “Most students in the country do not live in on-campus housing. The overwhelming majority rely on the same housing markets that non-students do.”

And those markets are increasingly expensive. In November 2023, the national median price for a rental was $1,967, up from $1,584 in January 2020, according to Rent.com’s December 2023 Rent Report. The increases are frequently higher in college towns, from 32 percent in State College, Pennsylvania, to 29 percent in College Station, Texas, from 2021 to 2022, Inside Higher Ed noted in September 2023.

Bottom line: American students are facing a housing crisis. And it’s affecting them not just financially but emotionally and academically.

As the 2023 fall semester began at the University of Washington (UW) Tacoma, Roseann Martinez was busy. Too busy. Martinez, a social worker and the university’s assistant director for student advocacy and support, was working to find housing for students. In the previous academic year, Martinez and her colleagues served roughly 100 students who were homeless or at risk of homelessness. This year was no different—and it’s a problem throughout the state.

In a January 2023 survey from Western Washington University and the Washington Student Achievement Council, 34.2 percent of college students in the state had experienced housing insecurity in the past twelve months, and 11.3 percent had suffered from homelessness. The numbers might be even higher at UW Tacoma. After the pandemic, there was “a huge uptick” in housing insecurity, says Mentha Hynes-Wilson, UW Tacoma vice chancellor for student affairs, who estimates that about 40 percent of students are now dealing with housing issues.

“We are an urban-serving campus—we are situated right downtown—and many of our students are coming from underrepresented populations,” Hynes-Wilson says. “Fifty-one percent are first-generation college students, 49 percent are Pell eligible, and 61 percent are students of color.” Students who are battling housing insecurity defy easy stereotypes, she adds. Her office has worked with veterans, autistic individuals, students over the age of fifty, and students who were previously incarcerated.

Housing prices have risen as people from costly Seattle, about thirty-three miles north, move south to Tacoma. The average rent for a downtown studio has jumped from $850 a month to $1,500 a month. “That’s the average,” Hynes-Wilson says. “That’s one room, 250 to 500 square feet.”

Scarce, expensive housing is also a major problem in parts of California, where as many as 417,000 students in the state’s three higher-ed systems—the California Community Colleges, the University of California (UC), and California State University—lack stable housing. Roughly one-quarter of community college students in the state are homeless, a 2023 Community College League of California survey found.

In pricey areas such as Berkeley and Los Angeles, students are struggling with a lethal combination of forces: inflation has driven up rental costs, residents have blocked new housing proposals, state funding increases have stalled, and labor and construction costs have soared.

This has resulted in intense battles for housing. Zennon Ulyate-Crow, a junior at the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), majoring in politics and minoring in legal studies, has seen this not just as a student but as a housing activist. He’s the founder of the UCSC Student Housing Coalition—an advocacy organization for students, by students—and the student housing policy lead for the UC Student Association. Because of the lack of affordable housing in affluent Santa Cruz, Crow has numerous stories of students vying for subpar high-cost units.

“Landlords will have open houses for places that are really health-and-safety violations—places that should not be allowed to exist—and they’ll have students lined up competing against one another,” Crow says. “I know people who have shown up in suits and ties to house openings and brought gifts to convince the people that they’ll be the best tenants ever.”

In his case, Crow and a group of five other students met with an agent at a local real estate company. She said she’d listed three houses on Monday; by Friday she’d received applications from more than seventy groups. Crow and his potential roommates then connected with a landlord who told them it was between them and one other group. Whichever one delivered a check first would get the house. “We got it to her, and we got the house, but that’s how insanely competitive it is, because there are so few options,” Crow says.

How bad is it? Crow says he saw a real estate listing for a boiler room in Santa Cruz. The price: $800 a month.

For many students, the lack of affordable housing is life altering. Some have rethought their college plans, opting for a community college or for working a job instead of going to college at all. Others have been forced to enroll part time, live farther from campus (sometimes without reliable transportation), and work longer hours, a US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) report notes. In the Hope survey, a student from Texas said that he worked full time at night, lived in a hotel, and struggled to study because of the noise.

“With housing insecurity, you can’t focus 100 percent on your education,” says Mary Jacobs, a licensed social worker and program director for NCS Scholars. “We’ve had students say that they’ll stay at the library until it closes, just so they can be somewhere safe.” Housing insecurity is also linked with other problems, such as food insecurity and poor sleep, which makes it difficult to focus.

“Students who are housing insecure are less likely to complete their degree and are at a higher risk for other basic needs insecurities,” declared the August 2023 BPC report. The lack of a degree also leaves students “more likely to face difficulties in repaying loans and default.” In a 2022 survey from Student Beans, a discount network for students, 36 percent of students said they’d thought about dropping out due to their financial situation. Those who’d endured housing insecurity were twice as likely to seek bank loans, more than twice as likely to shoplift, four times more likely to sell drugs, and five times more likely to get involved with sex work.

While students of all income levels are grappling with a housing supply crunch, low-income students are the most likely to face housing insecurity or homelessness. The challenges are particularly acute for students emerging from foster care, HUD states. Students of color are more likely to endure housing insecurity than White students, the Hope survey found, and LGBTQ+ students also face higher risks.

“The numbers for LGBTQ+ are extremely high,” Jacobs says. “A lot of times, the families don’t agree with their [children’s] gender identity or sexual orientation, and they kick them out of their home. A lot of abuse happens to LGBTQ+ youth. They need a safe space. And if they don’t have it, they get re-traumatized over and over again.”

Yet many students, whether they’re couch surfing or sleeping in the student union, are reluctant to accept help. Rachel Noble found this while working as a patient care advocate in the student health office at George Mason University. The campus is based in affluent Fairfax County, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, DC, yet Noble worked with multiple homeless students, including a mother living with her daughter in a car.

“They would often tell me that other people needed the help more than they did,” says Noble, now a licensed therapist. “I think it was partly selflessness but also embarrassment. There’s so much privilege on a lot of college campuses. One woman told me the only time she felt normal was in class. It was the only time she felt invisible.”

Many colleges and universities are working to address the problem. In May 2023, State University of New York chancellor John B. King Jr. announced plans to require a homeless liaison “to identify and support students who are unhoused or at risk of housing insecurity” at each of its sixty-four campuses. UC Santa Cruz provides legal advice to students who are having issues with their landlords, and universities such as Harvard; the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA); and the University of Southern California have student-founded, student-run homeless shelters. Some institutions are thinking outside (and inside) the box. In 2020, the College of Idaho opened two residence halls made from repurposed shipping containers. The dorms took eight months to build rather than the more typical two and a half years.

In September 2023, Governor Gavin Newsom of California signed a bill making it easier for the state’s public universities to build student housing. The legislation followed a February 2023 court ruling blocking a proposed housing project at the University of California, Berkeley. The university now plans to build 1,200 units of housing, including 160 for people who were formerly homeless.

In 2019, the Washington state legislature launched a program called Supporting Students Experiencing Homelessness (SSEH), which provides grant money to colleges and universities. More than thirty institutions now participate in SSEH, including UW Tacoma, which received a $100,000 grant in 2022. The university has used the funds for a variety of purposes, including setting aside two student apartments for emergency housing and funding HuskiesCare, an “online hub” with resources on housing, childcare, basic needs, mental health, and more.

Unique solutions such as SSEH are vital for protecting students. The BPC recommends policy reforms at the federal and local level to “unlock needed support for students struggling to access stable housing.” This includes letting students use the Federal Supplemental Educational Opportunity Grant (FESOG) to address housing needs. “Evidence shows that emergency micro grants and small support at crucial moments can be the difference between someone being able to pay their rent or being evicted,” Torres says. Other proposed solutions include giving public housing authorities flexibility to use federal funding for college students, allowing them to live in units financed by the federal Low Income Housing Tax Credit Program, and promoting zoning reform in college communities.

“College completion is still a fundamental part of the story of economic mobility in the United States,” Torres says. “A lot of research has shown that the students who are unable to complete their degrees, or whose studies are interrupted, do not enjoy the full benefits of attending college in their future wages and their ability to be economically mobile.”

Maria at Brooklyn College envisions a bright economic future for herself. Once she graduates, she hopes to earn a law degree and start multiple businesses. “Even though I have struggles, I’m motivated, and I’m going to make it,” she says. But in the short term, she has a more pressing task. After she graduates, when she leaves the NCS Scholars program, she’ll need to find housing.

Illustrations by Joan Wong

Getting Help from HUD

Certain federal housing assistance programs are open to students—though sometimes there’s a catch. For information on federal assistance, contact your local Housing and Urban Development (HUD) office (go to hud.gov/states). Here’s an overview:

Section 8 vouchers

Students may receive Section 8 assistance (a subsidy that’s paid to a landlord) on two conditions: 1) they live separately from their parents, and 2) they and their parents both meet the income requirements. The restrictions do not apply to students who are veterans, married, have a dependent child, or are twenty-four or older.

HOME Investment Partnerships Program

Students who qualify for Section 8 vouchers can occupy HOME-assisted rental units (HOME provides grants to state and local governments to create affordable housing for low-income households). Those units cannot be set aside for students, however, and students cannot receive preferential treatment.

Public housing

“Students can live in public housing if they meet the income restrictions,” HUD states. The catch: local public housing authorities sometimes exclude or deprioritize full-time students from their definitions of eligible “families.”

Chafee funds

States can spend up to 30 percent of their funds from the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program to help young people aging out of foster care address their housing needs. You can find info on the Chafee program at Benefits.gov.

Guaranteed Housing

For students in California, finding housing can be as challenging as taking exams. Intense competition for affordable housing can force students to pay high rents and live far from campus. To ease the anxiety, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), launched a unique initiative in 2022. The university guarantees four years of housing in university-owned residences for all incoming first-year students (and two years for transfer students).

The move followed the opening of several new residence halls and apartment complexes, including a seventeen-story high-rise. Other recent programs include the Center at 106 Strathmore, which opened in January 2023, and offers support—such as food programs, emergency funds, and rest spaces—to students facing basic-needs issues. UCLA has also expanded Bruin Hub, a program that provides “pods” where students with long commutes and housing-insecurity issues can study and rest. Challenges, however, remain. The University of California Regents delayed approval of a 545-bed residence in September 2023, citing the small size of the units: just 265 square feet for a three-student room.