Through These Walls

An educational journey once thought impossible shows the potential for restorative justice—and brings hope to a Maine prison

What are some of the benefits of higher education in prison?” Ten years after beginning my college journey from behind the walls of Maine State Prison, I have answered this question more times than I can count. As I step into the first semester of my doctoral program in conflict analysis and resolution in fall 2023, I find myself reflecting on the obstacles that I have surmounted, the work I have done with Colby College, the support I have received as I spearheaded initiatives to transform prison culture, and my ongoing efforts to expand opportunities for incarcerated people.

As the first incarcerated person in the United States to teach outside college courses, I am a living testament to the power of higher education in prison. Higher education in prison programming—and its immediate professional application through paid fellowships, internships, and employment—must expand as an avenue toward remaking the current system of mass incarceration from one that self-perpetuates to one that supports personal transformation and healing, which will help reduce the number of people in prison.

Like the majority of young Black men who find themselves ensnared in the criminal legal system, I came to prison without having finished high school. (Sixty percent of Black men who are incarcerated do not have a high school degree, as criminal justice professor Mike Tapia and coauthors write in the Justice Policy Journal.) I was a senior when my biological father died on the one-year anniversary of my foster mother’s death. I didn’t know how to deal with the emotional impact of having twice watched helplessly as someone I loved died. Instead of finishing school, I dived headlong into drinking, partying, and substance overuse, getting arrested within two weeks of turning eighteen.

Yet, I refused to be another Black high school dropout. I contacted the Maine Adult Education system about taking the General Education Development (GED) test. But, after a series of bad decisions, on the day I was scheduled to take the GED practice test, I was arrested for nearly killing two innocent people during a home invasion. During the twenty-two months I spent in the county jail facing multiple prison sentences that added up to four natural life sentences, I finally took the GED test. The day I received my GED diploma was the same day I received my fifty-year prison sentence. February 26, 2010. I was all of nineteen years old and confronting the reality of spending the rest of my life in prison.

During the first three years of my incarceration, I was angry, hurt, and silent—hopeless. I stammered whenever I started a sentence with a word that began with a vowel. Then I met Ephriam Keith Bennett, another incarcerated person. An older Black man from inner-city Chicago, a husband, father, and former business owner who had served honorably in the Army, he helped me realize I did not need to be engaged in illicit or violent activity to be a man. I started taking personal development programs—in art, music, emotional literacy, and anger management. I also took Alternatives to Violence Project workshops, which, as the project’s website explains, “examine how injustice, prejudice, frustration, and anger can lead to aggressive behavior and violence.”

When Mr. Lloyd, an elderly man I had come to care for, was nearing death, I got to know the hospice team, a group of mostly longtimers who care for sick, hurt, and/or dying people in prison. Warm washcloth, small bucket of water, and comb in hand, I removed food from Mr. Lloyd’s biker’s beard and worked out the sticky tangles in his hair. Then, I put a single braid in both his hair and his beard. If he was going to die, he was going to die in style. I subsequently joined the hospice team, training in patient care, compassionate presence, empathy, comforting touch, and ways to honor multiple faith journeys to become a state certified personal support specialist.

As I was running out of prison programming options, the prison’s college coordinator invited me to apply to join the next college cohort being funded by the Sunshine Lady Foundation, which supports higher education in prison and reentry programs. This allowed me to earn an associate’s degree in liberal studies from the University of Maine at Augusta (UMA). I then went on to earn my bachelor’s degree in liberal studies with a minor in history, with most of my classes taught in person by UMA professors. I had given up hope of making anything of myself when I received my de facto life sentence (the United States Sentencing Commission sets 470 months, or just under forty years, as de facto life). But my studies and service work helped me realize that even if I’m going to die within these walls, it doesn’t mean that I can’t do some good with my life. While I can never undo the harm that brought me to prison, I am still a human being, and I can work to interrupt the cycles of harm, pain, and trauma in the lives of others. I can pay forward what I can never pay back.

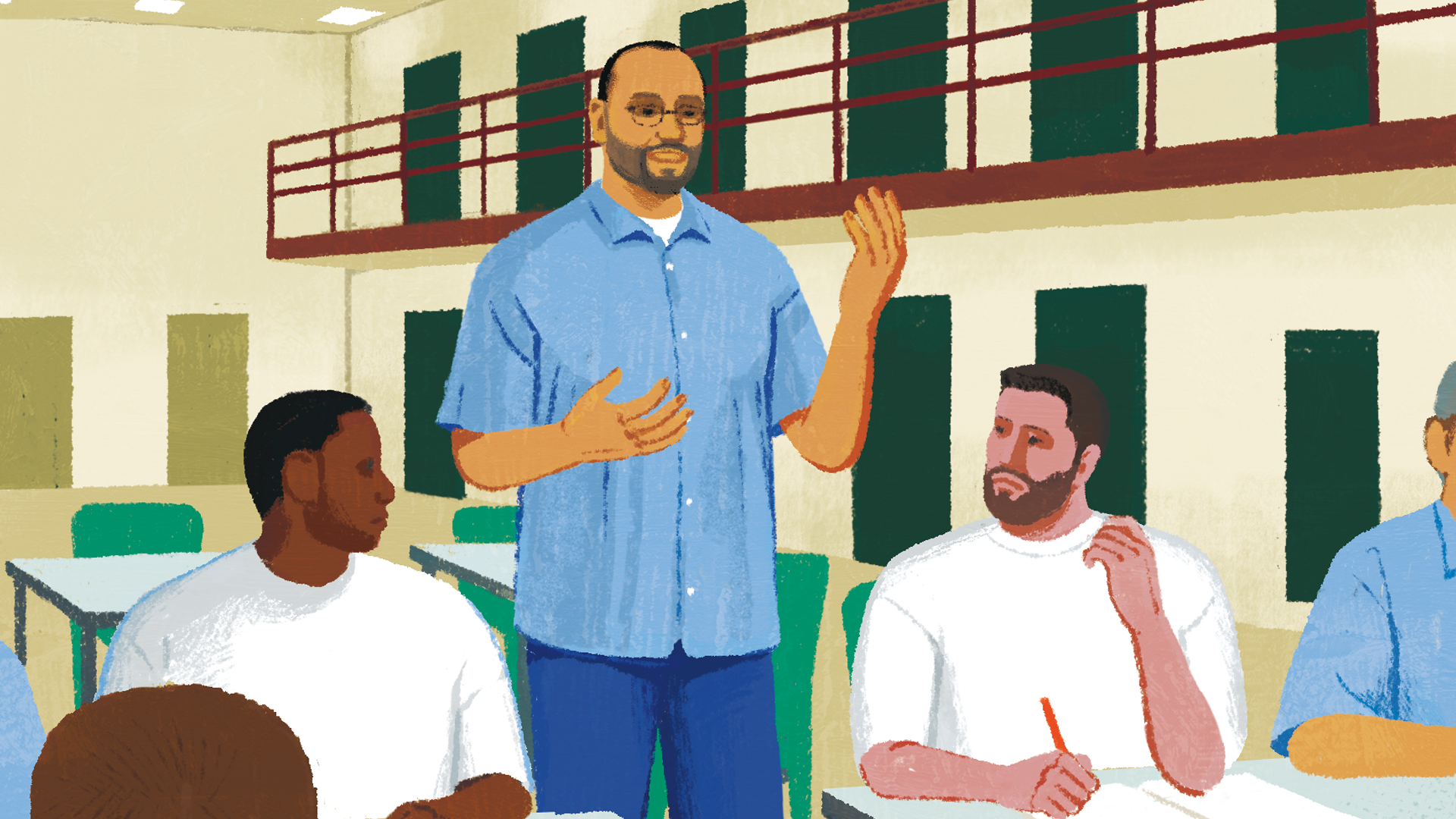

My development as a servant-leader, one who leads through a commitment to serving others, began when I took an introductory math course. I hate the subject for its inflexibility, but I’m really good at it, and the professor asked me to tutor other students. So, on Tuesdays, I (re)learned a litany of math skills, then on Fridays and Saturdays, I taught those skills to groups of four to six men. Whenever a test was coming up, the meetings would double in size and frequency.

I found a great deal of meaning and purpose in teaching. Yes, we did math. But we also did life. We talked through the struggle of attaining an education, how other incarcerated people we thought were our friends would disparage us, especially those of us serving long sentences: What are you getting an education for? You’re not getting out. If you do, you’ll be an old man. And a liberal arts degree? How’s that going to get you a job?

And worse: You think you’re doing the work in here that students are doing on the outside? There’s no way you would stand up against actual college students.

I just dug in and pushed harder. I took a full load of classes my first year, working five days a week in the prison barbershop, completing 150 hours of hospice training spread over nine months, tutoring on the weekends, and mentoring people through their emotional struggles in my spare time. “Don’t tell me what you can’t do,” Ephriam would say when I needed encouragement. “Let God tell you what you can do.”

Incredible determination and community support are required to obtain a college degree in prison. When I graduated with my associate’s degree, I reached out to my middle school social studies teacher, Kelly Taylor, one of the few people who had genuinely cared about me during my eight years in the foster care system. Kelly had written to me shortly after I was incarcerated—not to tell me what a monster I was but to remind me that God loved me and to encourage me to not give up on my education. After I graduated at the top of my class, I sent her a copy of my degree and graduation speech, along with a letter saying that her support had helped carry me through to this moment of celebration. As I went on to earn my bachelor’s degree, my college experience clarified a sense of purpose: the rest of my life would be dedicated to cultivating accountability, creating opportunities for repair, and facilitating healing in the aftermath of harm.

Near the end of my undergraduate program, one of my professors, UMA’s Ellen Taylor, commented on one of my papers that it was graduate-level work and that it would be a waste if I didn’t pursue the next step in my education. It was true—if I wanted to work to remove the post-release barriers to housing, meaningful employment, transportation, continuing education, mental and physical health care, and more, I needed professional tools and skills. I needed to understand how systems influence people, how policy governs systems, and what levers exist for peacebuilders to effect change and reduce harm within a system designed to be what criminal justice scholars Jennifer M. Ortiz and Hayley Jackey call “an intentional form of structural violence perpetuated by the state to ensure the continued oppression of the most marginalized groups in our society.” So, I put aside my insecurities and applied to graduate school at the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter School for Peace and Conflict Resolution at George Mason University.

In the middle of 2021, Catherine Besteman, an anthropology professor and abolitionist educator at Colby College, invited me to speak on a podcast for Freedom & Captivity, a statewide public humanities initiative that considers how society might reimagine approaches to security and justice. By now, I believed in the deep power of restorative justice (an Indigenous ethos that guides practices and processes seeking holistic repair of interpersonal harm through community-based cultivation of accountability in the person who caused harm, rather than the punishment-focused justice of the criminal legal system), but I had yet to develop my identity as a prison abolitionist. However, while speaking on the podcast about how restorative justice can—and must—be implemented as an avenue of meaningful accountability and repair in the wake of interpersonal harm, I realized that when we build the community capacity to do this work, the natural results will be the safe realization of prison abolition.

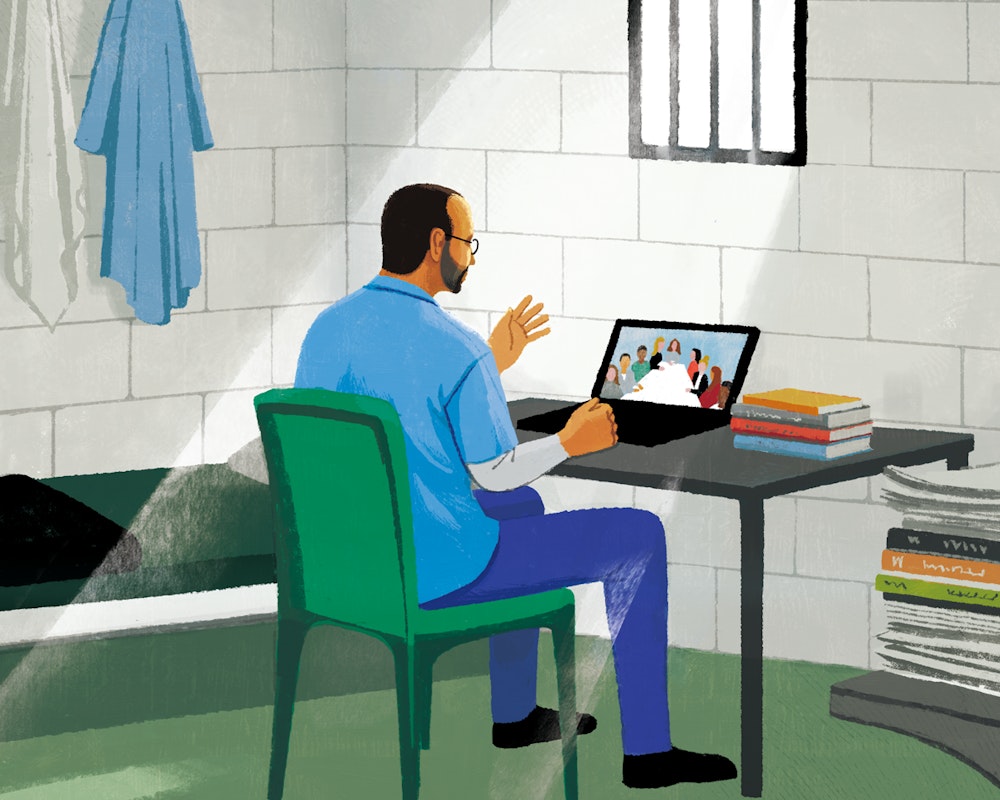

I then spoke at the Oak Institute for Human Rights at Colby College about my work as a currently incarcerated activist. Afterward, Catherine asked if I would be interested in co-teaching an upper-level anthropology course, Carcerality and Abolition, with her. My response was an immediate and excited yes. After receiving approval from Maine’s commissioner of corrections, Randy Liberty, to co-teach via Zoom, in the spring 2022 semester, I became the first incarcerated person in the United States to teach outside college students from prison. The course had fourteen students and met in a classroom at Colby, while I was present on Zoom. I was finally on my way to contributing to my outside community here in Maine, to providing care and guidance to young people in the same county where I had caused so much harm.

Catherine and I came to our partnership with very different teaching styles. Catherine wanted to ensure we offered rigorous engagement with the course materials, allowing students to play in the land of ideas. I wanted to trust that our students would immerse themselves in the materials on their own so that during class, we could focus on how the ideas we read about might be applied to create real change. I wanted students to consider the “so what” question, an approach I learned from UMA’s Robert Bernheim: “We have spent this time learning about the harms of the prison system and the need for restorative justice—so what? What does it mean to you? Personally, professionally, and academically?”

A course on psychosocial trauma and healing that I took at the Carter School informed much of my teaching practice. I knew what it felt like to be a student while also being valued as a colleague, seen as a human being, and honored as someone with expertise unique to my lived experience. I also wanted our students to feel seen, heard, and honored. Leaning into Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Catherine and I created a space of co-learning, in which both professors and students were student-teachers and teacher-students. We also incorporated restorative justice practices, opening and closing each class with the Indigenous practice of circle dialogue, during which each person responds to a question in order around the circle, honoring the choice to speak, pass, or hold a moment of silence. We opened class with a brief meditation or body movement, followed by a question like “How are you arriving today, in terms of the weather?” As the students took hold of this practice, they put forward questions like “If you were a breakfast, what would you be?” or, interestingly, “If you were water, what would you be and why?”

As the course progressed, we felt the power of community connection that is facilitated through restorative practices. As student Mairead Levitt shares, “There was no judgment or worry of embarrassment, which empowered me to truly be myself, and therefore be much more comfortable in class and in my learning journey.”

Other community-building elements we used included journaling throughout the semester, with students often sharing their reflections with the class, and the creation of class agreements during the first day, a collaborative effort that laid out the ways both instructors and students would participate in the course: speak with intention, listen with attention, honor one another’s voices, and honor ourselves. We discussed the question “What do you need from us as a whole for you to be able to show up in the fullness of who you are?” Everyone contributed answers: being OK with uncertainty, spending time in small groups to flesh out thoughts before returning to large-group discussion, being patient and courageous with one another, and being comfortable with silence. A strong sense of community was crucial to our being able to grapple with the powerful truths and emotions that might come up during discussions of hard topics, such as the devastating impacts of solitary confinement on prisoners and staff, and abolitionist feminist approaches to accountability and repair, which focus on social justice rather than incarceration, after serious interpersonal or sexual violence.

We began the course by examining how the current system of mass incarceration in the United States is firmly rooted in slavery. Guided by prison abolitionist visionaries Ruth Wilson Gilmore, Danielle Sered, and Tiyo Attallah Salah-El, and engaging with the work of formerly incarcerated intellectuals and revolutionaries such as Angela Davis and George Jackson, Catherine and I invited students to see the intergenerational nature of abolitionist work. We discussed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense and navigated between theory and practice, studying the works of journalist Victoria Law, social anthropologist Orisanmi Burton, and incarcerated abolitionist scholar Stevie Wilson. The course culminated in a final eight- to ten-page paper and a presentation on a topic of each student’s choice.

We taught the class twice, in spring 2022 and spring 2023, and Catherine and I emphasized to students that our work together extended beyond the classroom. One example is a Sunday night Zoom call student Matt Matheny had with me and Catherine. Matt asked us how, in a way that would repair harm and be restorative rather than punitive, he could support two friends who’d had their belongings stolen. “Our discussion helped me better approach that situation and prepare for similar situations in the future,” Matt says. “More than just teaching concepts and doing readings, this course showed me new ways to approach life, both inside and outside the classroom.”

As part of my teaching role, I received approval to hold office hours each week. I met one-on-one with students on Zoom to work through difficult ideas and emotions that arose in relation to course materials. For example, several students had survived sexual harassment and violence, and a few taught classes on sexual violence prevention. They struggled with the concept of restorative justice or an abolitionist future without prison time for people who commit sexual offenses. We addressed these topics in the classroom, but my office hours provided a space for deeper discussions. “I felt passionate about restorative justice, and also knew how hard it was to heal from sexual misconduct,” student Georgia Goodman says. “I still don’t have a definitive answer on how we deal with perpetrators of sexual misconduct, but talking with Leo helped me to explore the middle ground and understand that at the root of all the questioning we have is really just finding space for healing and love and support (for both survivors and perpetrators), and ultimately, our current carceral and penal systems do not accomplish that.”

Student Olivia Cella shared that, as someone who sees herself as privileged, she has often felt guilt around her mental health struggles. During our one-on-one discussions, though, she says, “I found a new voice by which to verbalize what I thought could never be articulated to, nor understood by, another person. [Leo and I] were both able to share tribulations we had each experienced—I felt heard.”

Student Josh Kim wrote in his class journal about how, as he walked back to his dorm to meet with me on Zoom one day, he felt exhausted by his workload. But during the call we discussed Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning and the purpose of our lives. “And boom,” Josh wrote afterward, “I’m looking at a man who has been stuck in the same box of a cell for the past fifteen years of his life. All the thoughts, worries, and frustrations from my life were reset from my mind in one big swoop. I still don’t know exactly what/how I feel about carcerality and abolition, but I know that this conversation with Leo is a step in the right direction.”

Most of what I have done in the past two years originally seemed impossible. When I started my master’s program, my admissions advisor and I could only dream about the possibility of my doing an internship. A year later, I was co-teaching a college course and doing a virtual internship with the Carter School’s Transitioning Justice Lab, primarily supporting research, presentations, and trainings on restorative justice and alternatives to incarceration. For one class meeting of Carcerality and Abolition in spring 2022, I even received permission to go to Colby in person, and the Department of Corrections’ head of security, who transported me, as well as Commissioner Liberty, took part in the lesson. Another day, the class met with me at the prison. The hope these accomplishments have given other people throughout this prison has risen to levels I never could have anticipated. It has been incredibly moving to be asked by another resident whether I am really teaching at a college somewhere and then to see his eyes light up when I say that yes, I am.

Applying my studies about restorative justice to concrete actions has also led to meaningful changes inside this prison. One example is the Earned Living Unit (ELU). Formerly the infamous supermax unit, the ELU is the prison’s least restricted unit, where residents live in community with each other. Creating the ELU began in 2021 when the warden asked the prison’s Restorative Practices Steering Committee, on which I serve, to compare Maine State Prison with Norway’s Halden Prison, which focuses on rehabilitation and aims to reduce people’s sense of being incarcerated by finding ways to simulate life outside prison. The foundational documents that guide the self-governance of the unit, which I helped create from my studies at the Carter School, are based in restorative justice practices. For instance, the ELU’s Monday evening house meetings allow for open restorative dialogue during which the thirty-plus men in the unit can speak about ongoing projects, offer ideas, share gratitude, and address conflicts. The men also divvy up chores and tend the massive garden that provides produce to the prison kitchen and outside food pantries.

We know that higher education in prison reduces recidivism: according to research from Emory University, the recidivism rate is about 55 percent for ex-offenders who finish some high school. The rate drops to 13.7 percent for those who earn an associate’s degree, to 5.6 percent for those who earn a bachelor’s degree, and to 0 percent for those who earn a master’s. But for that education to have more of a positive impact, people need to be able to apply their learning in a professional way while they are still incarcerated. The Alliance for Higher Education in Prison is leading the effort to make this happen through its Education in Action initiative. For instance, as currently incarcerated Alliance fellows, Victoria Scott and I are creating an infrastructure for how businesses and higher education institutions can partner with departments of corrections to create internships, fellowships, and employment opportunities that are paid at real-world wages and/or are college credit–bearing.

I am fifteen years into a fifty-year sentence. Without an opportunity to professionally apply my education, I almost certainly would have lost motivation to continue my trajectory of personal development, stagnating mentally and emotionally. When I completed my bachelor’s degree, I still had more than thirty-five years left to serve. I had no ability to transfer to a minimum-security facility, no way to move through the system, no way to meaningfully contribute to my family or outside community. I was facing a plateau on which I would start my journey of waiting to die. Now, due to outside employment, I have the ability to support my family, pay taxes for the first time, prepare for my hopeful eventual release, and work to open doors for others to do the same and also to be able to pay whatever fines, fees, restitution, child support, and victim compensation they might owe.

Community safety does not come through

incarceration. It comes through community building. Colleges, universities,

prisons, and other carceral institutions and organizations must create this

reality through courageous collaboration, transformative thinking, and

deliberate action. Systems do not correct themselves; they merely refine and

perpetuate themselves. We need systems transformation, and that is only

possible if we do it together.

Illustrations by Makoto Funatsu

The Alliance for Higher Education in Prison’s Education in Action

The goal of this initiative is to ensure people who are incarcerated have access to quality education and professional opportunities through apprenticeships, internships, fellowships, and other work-learning positions. To learn more and get involved, visit higheredinprison.org/info/education-in-action.