Mindfulness in Class and in Life

Mental health and emotional resilience alongside academic studies

In the fall of 2019, at the University of Southern California (USC), nine students died of causes that included suicide and drug use. The campus community was shaken by grief and called for action to support student mental health. It was my second semester teaching Introduction to Mindfulness, a two-credit undergraduate course I developed with the mind-body branch of USC’s Department of Physical Education. While the mindfulness course is not a substitute for professional advice, diagnosis, or treatment, it can offer tools for facing challenging situations, and as students in the class grappled with the loss of their friends and peers, they reflected that the class was helping them enhance their mental health, well-being, and resiliency. In interviews, survey responses, and personal reflections, students remarked on the personal growth, coping skills, and the feeling of connection to themselves, others, and the world around them that they experienced as a result of the course curriculum and mindfulness practices.

“It has been an interesting time at USC these last couple weeks with everything going on related to mental health,” Noah, a junior majoring in economics, wrote in a reflection. (Unless otherwise noted, names have been changed to protect student privacy.) To cope, Noah consciously applied tools from the course—meditating in the mornings, working on decision making, staying present, and holding his emotions lightly. “I have seen a big increase in my overall well-being, and I am looking forward to continuing the journey,” he wrote.

As educators confront the COVID-19 pandemic and systemic racial justice issues, addressing student well-being is more crucial than ever. In addition to ensuring trained mental health professionals and other psychological resources are available to students, campuses can incorporate well-being into the college experience and situate it as a priority by offering specific, for-credit courses that explicitly teach students tools to care for their mental health and navigate life. At USC, one way we do this is through the mind-body branch of the Department of Physical Education, which offers courses in yoga, stress management, and mindfulness, including my Introduction to Mindfulness class. Many students end up taking several mind-body courses, in addition to other department fitness and recreation classes, for a multidimensional approach to health and well-being. These courses foster community and belonging while contextualizing self-care within students’ busy college schedules, and the duration of a semester-long class allows for deep learning and accountability as students invest time and effort for a grade.

In April 2020, 80 percent of 2,086 college students surveyed by the nonprofit Active Minds said that the pandemic was negatively affecting their mental health, demonstrating just how much the current climate is magnifying the mental health challenges young adults were already facing. Prior to the pandemic, according to separate Active Minds data, 39 percent of college students reported that they experienced a significant mental health issue, and suicide was the second leading cause of death among college students. In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that nearly two-thirds of people surveyed across twenty-five states had experienced at least one adverse childhood experience. These can include violence, neglect, abuse, or death of a family member. Nearly one in six had experienced more than four. Spring 2019 surveys from the American College Health Association found that in the twelve months prior, 13 percent of the 67,972 respondents felt tremendous stress, 24 percent were diagnosed with anxiety, and 20 percent were diagnosed with depression. Thirteen percent said that they had seriously considered suicide. These issues can negatively affect lives and learning, as students may withdraw or have trouble focusing if they are struggling mentally. Indeed, the Active Minds survey from April found that, amid the pandemic, 76 percent of students have had trouble sticking to a routine, 73 percent have had a hard time getting enough physical activity, and 63 percent have struggled to keep connected with others. Eighty-five percent said that focusing on studies has been one of the hardest things about having to stay at home.

These statistics are not our students’ destinies. Rather, they reflect a crucial need to implement structured supports. Along with comprehensive campus mental health resources, mindfulness courses—whether in person or online—can offer students tools to thrive and focus on learning by cultivating awareness, processing emotions, and coping with difficult thoughts and stressors, in times of calm or challenge.

One student in my course, Zoey, had to move back in with her parents because of the pandemic and experienced anxiety over the uncertainty of her future plans. A senior business major, she found that sticking to a routine that includes meditation helped her focus on the present and stay productive. “Rather than worrying about what could happen and expending energy on stress about things I cannot control,” she wrote in a class reflection, “mindfulness has taught me to enjoy the days that I do have with my family and make the most of the additional time I’ve been given.”

Mindfulness courses—whether in person or online—can offer students tools to thrive and focus on learning by cultivating awareness, processing emotions, and coping with difficult thoughts and stressors, in times of calm or challenge.

Alongside the difficult emotions that are present amid calls for racial and social justice on campuses, mindfulness can help us compassionately bear witness to suffering and choose a wise personal and collective response. In a presentation and student panel I facilitated during USC’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Week earlier this year, Megan (Mae) Gates (her real name), a junior majoring in public policy who had taken my course, reflected on the role mindfulness can play in strengthening mental health in communities of color. A member of Alpha Kappa Alpha, the first Black sorority on campus, Mae has worked to have honest conversations about mental health in the Black community and ensure it is part of the impact she and her peers have on campus. “We have a lot of conversations among ourselves as Black women,” she told the audience. “What does mental health mean to us? What are the disparities that we had growing up? And how can we ensure that this becomes an integral conversation in our community and every part of life that we walk through?”

In the traditional sense, mindfulness is a type of meditation practice, and Introduction to Mindfulness is a secular course in which we explore formal practices of meditation—seated, standing, walking—as well as informal practices of bringing mindfulness into daily life, relationships, and decision making. During the course, students develop a personal meditation practice that progresses throughout the semester. The curriculum comprises five modules through which students explore the principles of mindfulness, the body, working with emotions, working with thoughts, and incorporating mindfulness in daily life. Students submit reflection forms at the end of each module and read a corresponding workbook, which I authored, that covers real-world topics including decision making, communication, relationships, and grief. In book groups, students read a book from the mindfulness field to deepen knowledge of practice and theory. Choices include selections by Jack Kornfield, Joseph Goldstein, Thich Nhat Hanh, Tara Brach, and Rhonda Magee.

Students also work in groups to explore strategies for incorporating mindfulness into an aspect of daily life, such as relationships, technology use, and social justice. This collaborative work creates supportive subgroups within the classroom community. The class has “provided me with a group of people that really care about loving people and building relationships,” Lana, a senior majoring in cinematic arts, said during an interview about her experience in the class. Her group explored the topic of relationships and focused on listening to others. “That’s been great because that’s when we can really talk about it together,” she said.

For exposure to a variety of styles and perspectives, students take an outside meditation class, which many do at a local studio (online during the pandemic) and continue to attend after the semester ends. I also invite guest speakers to class to discuss topics such as anxiety, grief, and intimacy and radical consent. Course assessments include a group presentation about their process and the impact of incorporating mindfulness into daily life, an exam on the principles of mindfulness, and reflection forms for each of the five modules—which include questions to deepen students’ understanding and application of the content.

Through their work in Introduction to Mindfulness, students build agency, strengthened emotional resilience, and became more open to kindness and joy. They learn practices to help them navigate difficult experiences, everything from a disappointing grade on an assignment to a breakup, the loss of a friend or family member—or a global pandemic. To gauge student growth and learning in the course, I conducted surveys across the three fall 2019 classes at weeks one, five, and fifteen to establish a baseline, initial progress, and end-of-course impact. In the week-fifteen survey, 92 percent of students responded that they felt the course “much” or “very much” affected their capacity to cope with challenges. They also gained confidence and developed a stronger self-image.

Steve, a senior majoring in business who took my mindfulness course in fall 2019, recently sent me an email with the subject line “Meditation saved my life.” He wrote about how tough 2020 has been for him, including feeling suicidal, losing friends, and losing his full-time job offer because of the pandemic. In the midst of his difficulties, he remembered the mindfulness lessons, practicing meditation to focus on appreciating what he did have. “I started to regain confidence and happiness in myself,” he wrote. “I started to realize that happiness comes from within, and not through external things. I am improving and starting to gain a little bit of hope.” In combination with professional help—in Steve’s case I recommended he seek such assistance, provided him with resources, and also notified the campus mental health help line—mindfulness can offer tools to navigate challenges students face.

In Introduction to Mindfulness, students learn the RAIN technique to recognize what emotion is present, allow it instead of pushing it away, investigate how it feels in the body, and hold it with nurturing kindness and nonidentification (treating it as the impatience, rather than my impatience). Known as affect labeling, the process of naming emotions has been shown to diminish emotional reactivity by stimulating the prefrontal cortex region of the brain and disrupting emotional amygdala activity. Students correspondingly build resilience to cope with stressful thoughts and find that instead of suppressing difficult emotions, they are able to sit with and process them. In the week-fifteen survey, 89 percent of students said the course “much” or “very much” improved their capacity to bounce back from challenges. This capacity leads to more responsiveness—rather than reactivity—when navigating difficulties.

“I’m someone that really feels emotions when they’re happening,” wrote Mia, a junior majoring in cinema and media studies. “By paying more attention to identifying my emotions, I am able to begin the process of working with them and not letting them just control me.” After the death of their classmate that fall, Mia and her friends got together and at one point started laughing about something. They immediately felt guilty. Mia told her friends about our class discussion on the idea that the heart is big enough to hold it all—the joy with the sorrow. In her reflections, she shared that hearing this helped her friends cope with the complexities of grief.

Comparisons of the week-five and week-fifteen survey responses indicated that high anxiety levels among the students in the mindfulness course dropped from 51 percent to 28 percent. Though the percentage of students who experienced depression didn’t change (31 percent), all students who did experience it remarked that the course increased their capacity to cope. The number of students who felt they “much” or “very much” had tools to cope more than doubled, from 15 percent to 41 percent. This was also true for anxiety, with the number of students who felt they could “much” or “very much” cope increasing from 38 percent to 74 percent.

It wasn’t that their outer circumstances had changed—rather their relationship to their challenges had. Eric, a sophomore psychology major, wrote that mindfulness helped him alleviate depression and anxiety and that his meditation practice had flourished. Over the semester, and with a therapist, Eric worked through a childhood trauma to gain power in defining his identity on his own terms. “My past doesn’t define who I am,” he wrote in a personal journal entry he shared with me. “But my past has certainly shaped who I am today. My pain has cracked my heart open wide. . . . There is so much more to me. I am much more than pain.”

As students learned tools for improving mental health and emotional resilience, they also noticed they were more open to kindness and joy and more aware of things for which they were grateful. The number of students who responded that they “often” or “very often” engaged in self-criticism decreased from 54 percent in week five to 36 percent by week fifteen. Correspondingly, at week five, 33 percent of students said they rarely spoke to themselves with kindness. By week fifteen, this number had decreased to 8 percent—and 81 percent attributed an increase in kind self-talk to the course. “I began to speak to myself with kinder thoughts, and a kinder voice for myself emerged,” Lana wrote. “I held each thought lightly and delicately, without judgment.”

Introduction to Mindfulness is not a silver-bullet class designed to save anyone, and individuals facing depression, anxiety, or other mental health issues should consult a licensed professional. Rather, the course is an invitation to a field that teaches students tools to navigate their experiences with awareness, curiosity, kindness, and openness. As my students have learned more about mindfulness, they have wanted to share the practice with those they care about. Many recommended the course to friends, shared the workbook with their parents, or took meditation classes with family and friends.

“I’m really taking my hardest classes to date, and I have so much on my plate,” Devin, a business major, remarked in an interview. The mindfulness class “is like a weird gap in my really busy schedule today where . . . I’m doing something for myself instead of doing something for my GPA or someone else.”

Situating a mindfulness course within the college day provides a safe space for students to build mental health and well-being practices among a community of their peers over a sustained period of time. This can be done in-person or in an online community. Though it may be difficult to be a college student in today’s society, no one has to navigate it alone. Institutions can include spaces where students explicitly learn resilient coping skills to manage whatever challenges arise—not as a one-time event but as a structured, proactive, comprehensive response to a clear and continued mental health need. In the wake of the tragedies at USC in fall 2019 and others throughout the country, in the face of the pandemic, in the urgent calls for racial justice, and with unknown challenges on the horizon, it is my hope that more universities, in addition to ensuring their campus offers robust mental health services, situate well-being courses alongside academics. This can even be structured as a well-being general education requirement so all students have the opportunity to build the mental and emotional resilience to fully thrive.

“People run on such high stress, and being mindful isn’t usually part of their daily discourse,” Mia said in an interview. “Having the opportunity to learn it in a class setting, where you’re kind of forced [to learn it] but also it’s not demanding or homework-intensive—having every student take this would be so helpful.”

Many thanks to student researchers Shayla McPherson, Cambria Peterson, and Sudhakar Sood for their diligence in interviewing students in the mindfulness course.

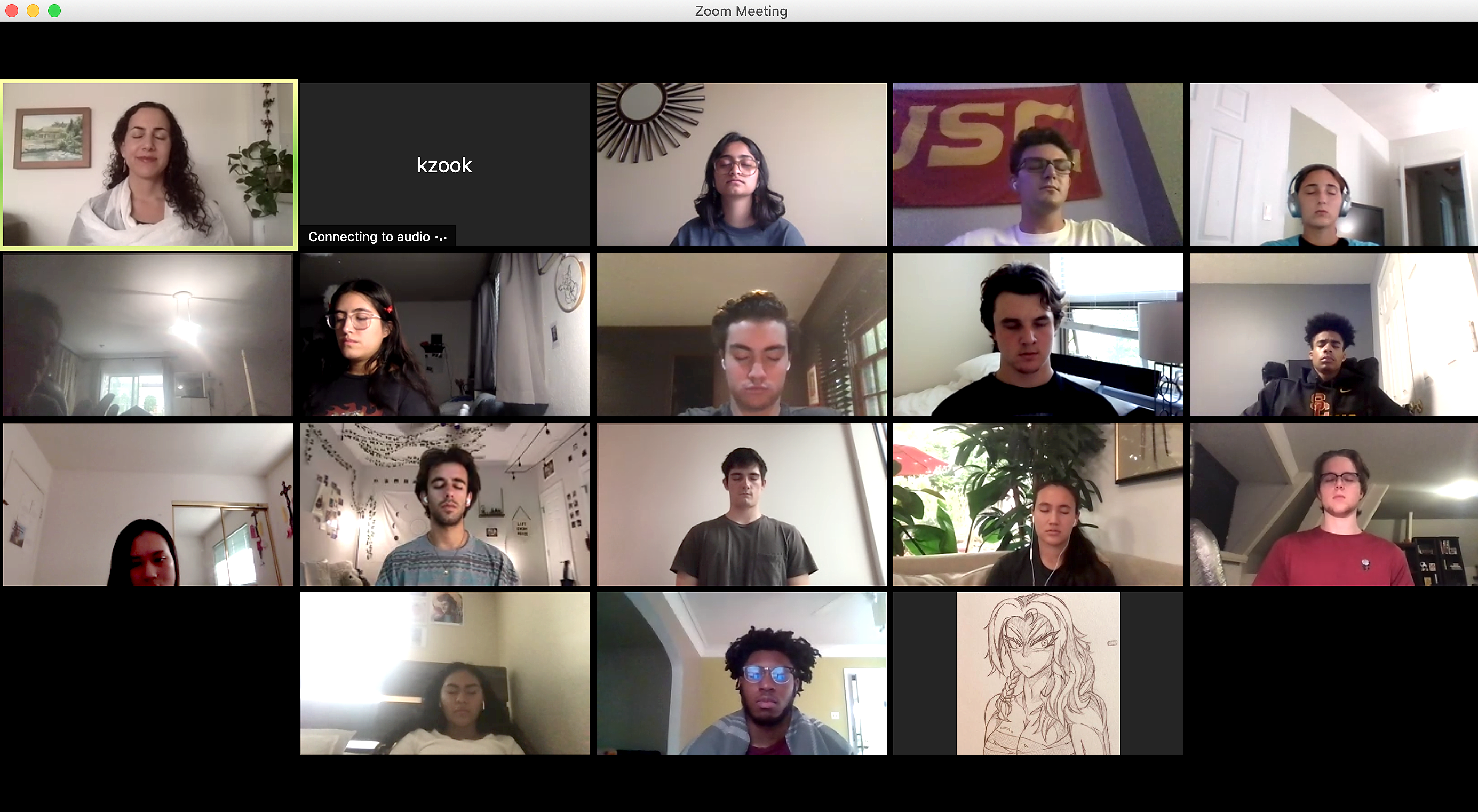

Photos courtesy of University of Southern California/Gus Ruelas and Linda Yaron Weston