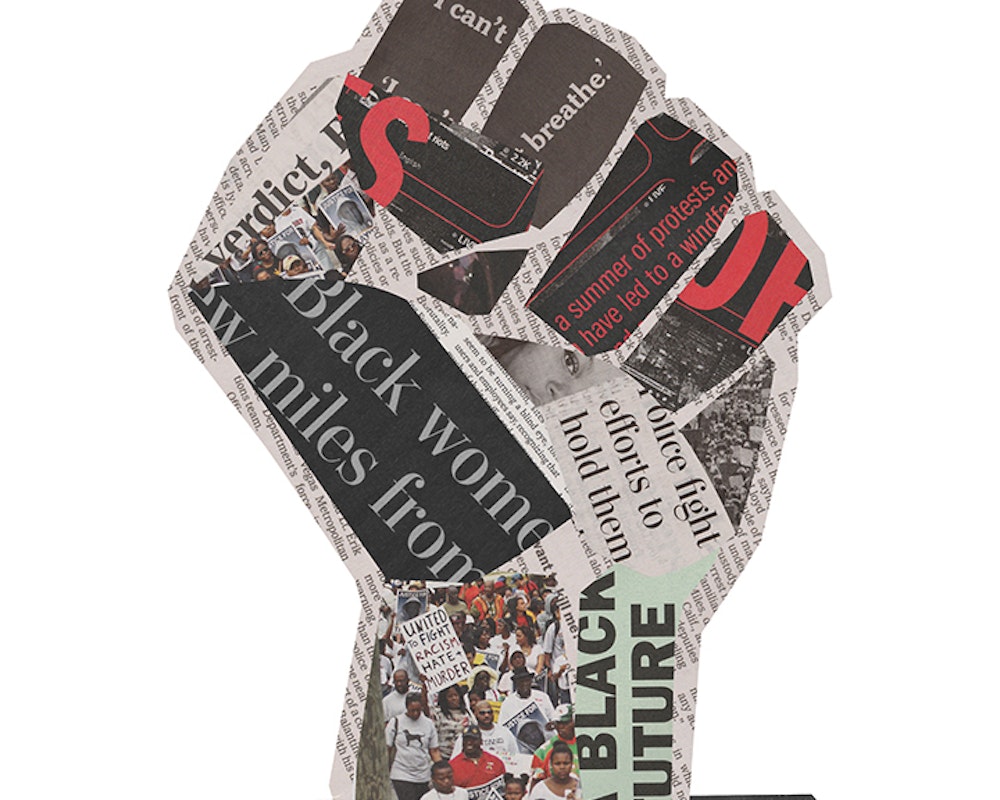

When the Outrage Subsides

Staying committed to ending racism and racial inequity

Continued racial and social injustices—including hate crimes against Asian Americans and other racially minoritized groups; the mounting loss of Black lives from police violence; mass shootings that affect communities of color; efforts to disenfranchise voters of color; and the unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic—are heightening awareness of why we must stay focused on racial inequity and racism in our society and in higher education.

Many of these racial inequities were born from policies and practices that promoted a false belief in a hierarchy of human value and resulted in slavery, conquest and colonialism, and the genocide of Indigenous peoples. These acts of injustice actively sought to exclude, marginalize, and oppress. The contemporary policies and practices resulting from these historical legacies demand system-changing responses and explicit attention to structural inequality and institutionalized racism.

Many educators have asked about the role of higher education in eliminating racism, how we can change our own racialized practices, and how we can build more just and equitable institutions. But are we willing to stay committed to the long-term work necessary to dismantle racism within our institutions and communities when the outrage subsides?

In January 2020, Estela Mara Bensimon, Lindsey Malcom-Piqueux, and I released our book, From Equity Talk to Equity Walk: Expanding Practitioner Knowledge for Racial Justice in Higher Education. We are all deeply committed to eliminating racial inequities and racism in higher education. As the book title indicates, we are also concerned that equity has become a buzzword in higher education without the intentionality necessary to change practices, mindsets, and institutional cultures for equity-conscious transformation. Colleges and universities need to embrace not just the equity talk but also the equity walk.

When we presented on our book during the 2020 annual meeting of the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), many of the educators in the audience were already interested in learning how to advance their work on racial equity. Most didn’t need convincing of why they should focus on achieving equity in higher education. Many nodded in agreement when we stated that most colleges and universities have limited clarity on individual and shared equity goals, that existing resources are inadequate to achieve equity-conscious transformation, and that the focus should be on improving the process for achieving equity in student outcomes, being race-conscious, and implementing systems for identifying and addressing racialized practices.

However, our goal for writing the book was not just to reach equity advocates but to reach those who are—as we quote Professor James Gray in our book—“first-generation equity practitioners” struggling with their own racial literacy. If we are to achieve equity goals and become equity-minded practitioners, we must build the capacity of educators to engage in processes for transformation.

In an AAC&U survey of 119 college and university presidents conducted in summer 2020, 80 percent of respondents believed that student activism would increase on campus as a result of the killings of Black people and the growing national movement for racial justice. Acknowledging the urgent need to address systemic racism within higher education, the report found that, whereas presidents’ short-term planning is focused primarily on dialogue and communication across stakeholder groups—and with students, in particular—long-term planning is focused on structural change. The long-term approaches that respondents cited range from “strategic hiring and curriculum reform to broad interrogation of institutional practices and policies in order to [identify] inequities and strategic planning efforts to address them.” In an AAC&U survey of 707 campus leaders conducted in October 2020, 57 percent viewed diversity, equity, and inclusion as the top strategic priority for their institution. This response is not surprising given the growing diversity in the undergraduate population and the increasing disparities in educational outcomes for marginalized and racially minoritized students. The share of undergraduate students who identify as a race other than White increased from approximately 30 percent in the 1995–96 academic year to about 45 percent in 2015–16, according to a 2019 report from the American Council on Education.

Educators must elevate anti-racism as a priority that higher education must take on if we are ever truly to be the just and good society we imagine ourselves to be. Educators must acknowledge that racism exists within higher education. We must identify and eliminate racialized practices that are both apparent and subtle. And we must understand why and how racial inequities are the result of racist policies and practices, as well as how the false belief in a hierarchy of human value has created a system of privilege that fuels division and feeds biases and preconceived notions of student success.

The reality is that many educators have difficulty engaging in processes for identifying racism and racialized policies and practices. They struggle with being race-conscious and with interrogating their own practices and structures. Campus leaders often invoke equity, diversity, and inclusion as values they hold dear. However, their embrace of equity often fails to turn into action and transformation if they cannot recognize the racialized consequences of everyday practices they take for granted.

To walk the equity talk, education leaders must admit to not always knowing how to address racism. In our book, we provide several actions that first-generation equity practitioners can take:

• Examine your perceptions of equity and develop new language.

• Learn to frame racial inequality in educational outcomes as a problem of institutional underperformance rather than student deficits.

• Develop a process to repair the effects of past exclusionary practices.

• Stop skirting around race by using coded language like “underrepresented,” “at-risk,” “vulnerable,” and “first-generation” when you are actually speaking about Black, Latinx, Indigenous, Asian American, and other racially minoritized students.

Typically, institutions present student outcomes data in the aggregate, obscuring whether and where inequities exist. We also must acknowledge the bias and privilege inherent in the ways we define equity gaps. Most often, when presenting student success data, the performance level of students from a majority demographic group is labeled the aspirational goal for all students. Educators declare success in closing equity gaps when marginalized and racially minoritized students reach the same performance level as majority students. But doesn’t this process for identifying equity gaps center whiteness as the norm and the definition of excellence for all students, reinforcing notions of privilege and racism with our systems, structures, and policies for student success? Defining excellence shouldn’t reinforce the standards of the dominant culture but should reflect the diversity of student experiences, represent a culturally responsive approach aligned with the institution’s values and goals, and emphasize what it means to be race-conscious.

Cultural change requires a collective effort among higher education administrators, faculty, staff, and students. Campus leaders need to understand and examine the narrative about race at their institutions and be honest about what needs to change.

As a leader of the push for racial equity in higher education, I want to meet educators where they are on their equity journeys while acknowledging the current sense of urgency for change. So, again, I ask: When the outrage subsides, are you willing to stay committed to the long-term work necessary to dismantle racism and racialized practices within our institutions? I am.

Illustration by Kendrick Kidd