Tenure, Contracts, and Mentorship

How two universities reimagined support for contingent and adjunct faculty

December 20, 2021

In partnership with AAC&U, the University of Southern California’s Pullias Center for Higher Education gives annual Delphi Awards of $15,000 to two institutions that are taking action to implement effective and sustainable programs to improve conditions for non-tenure-track faculty. AAC&U and the Pullias Center are grateful to the Teagle Foundation for their generous funding of the award and to the TIAA Institute for funding the award beginning in 2022.

Below, faculty and administrators from the 2021 Delphi Award recipients—the University of Denver and Worcester Polytechnic Institute—share their models to enhance job security, improve quality of life, and provide mentorship opportunities for non-tenure-track faculty. Read case studies about their work on the Delphi Award web page or join the campus representatives at AAC&U’s 2022 Annual Meeting for an in-depth discussion.

A Tenure Track for Teaching Faculty at Worcester Polytechnic Institute

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in March 2020, college and university faculty put much of their work—research, service, professional development—on hold. But not their teaching.

At Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI), a private university in Massachusetts focused on engineering and technical education, non-tenure-track teaching faculty were essential to moving the curriculum online and supporting students through teaching, project advising, and mentoring. But later that spring, when it was time to renew contracts for these faculty, uncertainty about enrollment and tuition revenue delayed the process.

“Not only was the teaching faculty’s value more obvious than ever, but their precarity was more obvious than ever,” says Kristin Boudreau, professor and chair of the WPI faculty’s Committee on Governance.

For more than a decade, faculty and administrators at WPI have been changing policies to better support non-tenure-track faculty (NTTF). In 2009, the university was increasingly relying on adjunct and contingent instructors, but these instructors had no contracts, no voting privileges in faculty governance, no consistent professional titles, no formal procedures for evaluation or promotion, and few protections for academic freedom. “Conditions were highly inequitable and clearly incompatible with the value of our teaching faculty to the institution,” says Professor Mark Richman, who served as secretary of the faculty from 2009 to 2012 (and is currently serving a third term). “It was clear to faculty governance, and especially to non-tenure-track faculty, that we had to begin moving the institution forward.”

Between 2009 and 2012, the faculty addressed several of these inequities. They established more consistent titles, promotion criteria and processes, evaluation procedures, and hiring protocols for non-tenure-track faculty members. In 2012, with support from the administration, those changes were accompanied by a substantial raise in salaries for NTTF.

However, the teaching faculty still lacked access to tenure, solid long-term contracts, and voting rights. In 2018, the newly elected secretary of the faculty, Professor Tanja Dominko, appointed a task force of five non-tenure-track faculty and five tenure-track faculty to reimagine the status of NTTF. Cochaired by Richman and teaching professor Destin Heilman, the task force interviewed department chairs and deans, attended departmental meetings, and hosted open town halls with faculty on and off the tenure track.

“That’s what engineering design is about,” Boudreau says. “Identify the problem, and before you formulate a solution, you get the perspectives of as many people as possible.”

Using a preliminary report presented by the task force in November 2019, WPI’s faculty governance and a newly formed NTTF Council worked with the provost to formulate a three-pronged solution: establish a tenure pathway for 40 percent of the teaching faculty, provide secure long-term contracts for all full-time teaching faculty, and welcome full governance participation regardless of tenure status. They developed new tenure criteria for teaching faculty that are rigorous, aspirational, and focused on what teaching faculty do to improve student learning.

As faculty and administrators discussed the proposed policy changes, many came to see that the status and value of tenure would not be threatened, that financial flexibility could be maintained without relying on layoffs, and that all faculty would have a stronger role in university governance. Nearly everyone agreed that education flourishes when faculty members are protected by academic freedom and can focus on their teaching from a position of security.

“Faculty feel the need for academic freedom every day,” Boudreau says. At WPI, every undergraduate student participates in a faculty-mentored project, often at project centers embedded within communities around the world. “It takes a lot of faculty labor and advising. It’s unscripted. We encourage our students to take risks, and we want faculty to take risks.”

In January 2021, in a nearly unanimous vote, the faculty approved a tenure pathway for full-time NTTF based entirely on teaching practice and teaching innovation. In a second vote in May 2021, the faculty approved secure long-term contracts that include the expectation of reappointment and prevent full-time faculty members from being terminated “at-will” without a cause or exigent circumstance. At the same meeting in May, the faculty approved full governance and voting participation for all full-time teaching faculty members. With support from the president and provost, the board of trustees approved all three actions over the summer.

“It sounds easy when you look at what we accomplished,” Dominko says. “But this is not an easy path, regardless of the ethical value of the argument you’re making.”

Secure contracts and full inclusion in faculty governance have been transformative for WPI, and faculty members are looking forward to the first inclusive faculty elections in decades. “Our efforts solidify the bond between the tenured, tenure-track, and contingent faculty, and we hope they set an example for others in higher education,” Richman says.

In August, the first fifteen teaching faculty were appointed to the new tenure track. “Our faculty can take bigger risks, be bolder, and teach with more conviction,” Dominko says. “Our students are sure to follow.”

Institutionalizing Faculty Mentorship and Support at the University of Denver

Before 2015, most non-tenure-track faculty at the University of Denver (DU), a private university in Colorado, were lecturers on one-year contracts with few opportunities for promotion. That year, the faculty senate and board of trustees approved new professional tracks, longer-term contracts, clear pathways for promotion, and more inclusion in campus governance for NTTF.

DU now has six professional lines for faculty based on their disciplines and responsibilities: clinical faculty, teaching faculty, research faculty, professors of practice, library faculty, and visiting and adjunct faculty (called “teaching and professional faculty”). Non-tenure-track professors in these lines are hired as assistant professors on renewable contracts of up to five years, while faculty promoted to full professors have seven-year contracts.

Establishing tenure and promotion pathways for non-tenure-track faculty is just the first step in creating a more stable and supportive environment for faculty and students. “Now you’ve got those lines, what happens next?” asks Laura Sponsler, clinical assistant professor of higher education. “Success is really in the implementation and institutionalization.”

Sponsler was one of the first faculty members hired in the clinical professor line. “When I showed up on the first day, no one knew what that meant,” she says. The lack of shared language around faculty roles made “it more difficult to develop consistent policies and procedures to support faculty and recognize all the different ways they contribute on campus, in research, or in our community.”

Since the new hiring and promotion policies were approved in 2015, DU faculty and administrators have established several structures to support non-tenure-track faculty:

Hosting Annual Workshop Panels. Since 2016, the faculty senate has cosponsored an annual workshop where faculty clarify pathways to promotion, share best practices, and connect with others across the university.

Convening an Ad Hoc Committee. In 2017, a group of faculty and administrators formed an ad hoc committee to help faculty reflect on their experiences and prepare for promotion processes.

Establishing a Permanent Administrator Position to Support Faculty. The university appointed Kate Willink as vice provost for faculty affairs in 2019, making her the university’s first permanent administrator dedicated to institutionalizing a commitment to improving conditions for faculty.

Willink and Hava Gordon, associate professor of sociology, have researched the work life of tenured associate professors. In interviews, tenured faculty say they see the inequitable effects of career contingency and precarious labor on their nontenured and adjunct colleagues and graduate students. They also have an increased sense of the financial insecurity of higher education institutions. Together, these factors amplify broad perceptions of collective precarity across academia, even among tenured faculty.

“People often judge the safety or the health of an ecosystem by how the least powerful folks are treated,” Willink says. “They assume that is going to be part of their lived experience.”

This instability and precarity among faculty trickles down and “can lead to instability for students,” Sponsler says. “If you have a happier, healthier faculty, they’re going to be more available for their students.”

Mentoring and Onboarding across Rank and Series. In summer 2020, a group of teaching and professional faculty hosted a symposium on creating collaborative department cultures and climates. The work from that symposium launched the Mentoring and Onboarding Across Rank and Series (MOARS) initiative, which has facilitated welcome events for new faculty, mentoring groups, and learning communities for instructors. “People still live in their departments, and their satisfaction and experience are governed in the department,” Willink says. “We’re trying to make sure that we could really attend to the climate and the culture in the departments.”

The work to improve mentorship led to the creation of a detailed chart that helps mentors and mentees continue building support structures across a faculty member’s entire career. “I’m really proud that we made 250 faculty less contingent in 2015,” Willink says. “But this is a whole other definition of not being contingent—recognizing how can you grow, thrive, and contribute throughout a whole career.”

Using Asset-Based Language to Describe Faculty. There are more than 150 different terms that colleges and universities have used to describe non-tenure-track faculty, and choosing the right ones can make a difference. “The way we talk about things affects how we see them,” Sponsler says.

In April 2020, the faculty senate approved using the term teaching and professional faculty, which focuses on the assets that faculty bring to the campus, instead of terms like non-tenure-track faculty and contingentfaculty that highlight perceived deficits.

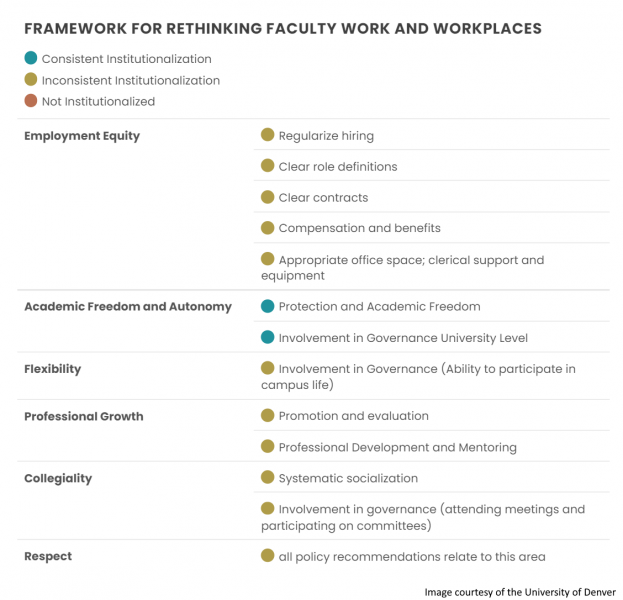

Creating a Detailed Framework to Assess the Institutionalization of Support. Taking what she learned from the various other initiatives across campus, Sponsler released a white paper in January 2021 that helps the university assess its work to support faculty development, career advancement, and mentoring. The white paper includes a framework for examining how consistently the university supports faculty across six areas: employment equity, academic freedom and autonomy, flexibility, professional growth, collegiality, and respect (see the figure below for the full framework).

“The framework talks about what it means to be respectful and inclusive of faculty work,” Sponsler says. “Are we consistently practicing these things no matter where you work at DU?”

Having a common language has also allowed administrators and department chairs to share data across the university, and helps departments and faculty members to evaluate their own work. “Before this, we didn’t really have a mirror to hold up to ourselves,” Willink says. “Is this part of the muscle memory of our institution? We have been trying to make sure that supporting faculty is not an afterthought but just how we do things.”

The framework includes three levels of achievement—consistent institutionalization, inconsistent institutionalization, and not institutionalized—for each area of faculty support. “We’re not outstanding in all categories,” Sponsler says. “But that’s the point. It takes a while to transform higher education, and this can be a very significant transformation for the faculty.”

This framework was informed by prior work from Judith M. Gappa, Ann E. Austin, and Andrea G. Trice in Rethinking Faculty Work: Higher Education’s Strategic Imperative (Jossey-Bass, 2007), and Adrianna Kezar in Embracing Non-Tenure Track Faculty: Changing Campuses for the New Faculty Majority (Routledge, 2012).