An Untapped Equity Resource

Higher ed can leverage assessment to address student enrollment and completion disparities

June 1, 2022

Read the Chronicle of Higher Education or Inside Higher Ed and invariably you find an article regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). DEI is a topic of numerous news articles, journal articles, books, and conferences—rightly so. While higher education has been touted to be the great equalizer for people in the United States, the playing field has not been leveled for everyone. In 2019, the six-year graduation rate for Asian American and White students was 74 percent and 64 percent, respectively, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, while the rate was 54 percent for Hispanic students, 51 percent for Pacific Islander students, 40 percent for Black students, and 39 percent for American Indian/Alaskan Native students.

These lower completion rates for Black people, Indigenous people, and other people of color (BIPOC) continue to limit career aspirations and life opportunities. In 2019, people ages twenty-five to thirty-four who held a bachelor’s degree and worked full time earned a median annual income of $55,700, according to the National Center for Education Statistics, while those in the same age group working full time with only a high school diploma had a median annual income $35,000. Imagine how large the difference in earnings between these groups would be after a forty-year career. That’s a pretty big chunk of change that could positively affect many lives.

Institutions of higher education have created various programs to improve BIPOC enrollment and graduation rates, including mentoring efforts, partnerships with high schools, and college admission visits to under-resourced schools with large numbers of students from low-income backgrounds. While these types of programs can help address enrollment and completion disparities across student populations, they don’t take advantage of an often-untapped resource: assessment. Yes, assessment! Assessment, which includes developing educational outcomes and then collecting and analyzing data related to those outcomes, is typically viewed as a tool for measuring student learning, student achievement of educational program outcomes, and ongoing student improvement in reaching learning goals, but it can also be a tool for advancing equity in higher education.

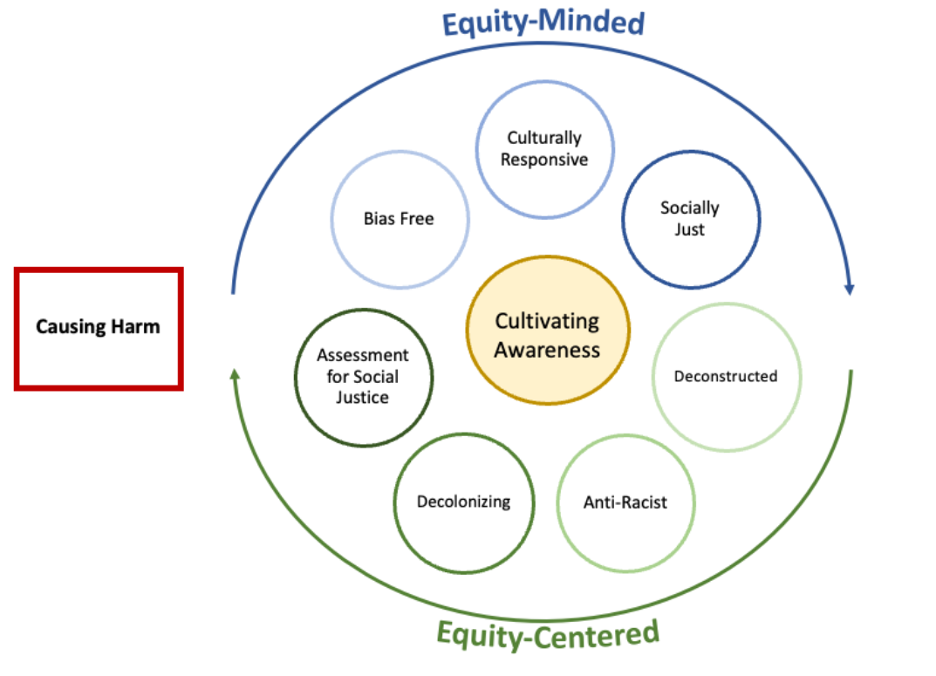

In 2016, educational researcher Jan McArthur coined the term assessment for social justice. She argued that assessment can support social justice in two ways. First, assessment can, and should, be implemented in a way so that the assessment process does not further inequities. Second, assessment can be used as a vehicle for social justice. Two of us authors, Anne Lundquist and Gavin Henning, furthered McArthur’s concept in 2021 by creating an equity-minded and equity-centered assessment framework, pulling together into one model various concepts related to the integration of equity and assessment. These concepts include bias-free assessment, culturally responsive assessment, socially just assessment, deconstructed assessment, anti-racist assessment, decolonizing assessment, and assessment for social justice.

While literature is emerging regarding the intersection of equity and assessment, few examples exist of this work in practice aside from equity case studies collected by the National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment (NILOA). Therefore, to better understand what equity-centered assessment practices are being implemented in higher education, the four of us authors created the Equity-Centered Assessment Landscape Survey, the first-ever survey of equity-centered assessment practice. The survey asked higher education assessment professionals about their attitudes toward integrating equity efforts with assessment practices. The survey also asked respondents about types of equity-centered assessment strategies and practices in which they might be engaging. The research team collaborated with a variety of higher education organizations that helped disseminate the survey and results. The survey partners included NILOA, the American Association of Colleges and Universities, the Association for the Assessment of Learning in Higher Education, ACPA–College Student Educators International, the Assessment Institute, the Canadian Association of College and University Student Services, the Council for the Advancement of Standards in Higher Education, NASPA–Student Affairs Professionals in Higher Education, and Student Affairs Assessment Leaders.

In July 2021, we sent survey invitations via a web-based survey platform to listservs for higher education assessment professionals. The various survey partners also promoted the survey through their regular communications and social media channels. Altogether, 568 people participated in the anonymous survey. Sixty-one percent of participants worked in academic affairs and 27 percent worked in student affairs. The respondents primarily led assessment efforts at the institutional, divisional, or departmental level and held titles such as director of assessment or vice provost for institutional research. Most had been implementing assessment for more than ten years and worked at midsize to large public universities. More specifically, 54 percent of respondents were staff members, 23 percent were faculty members, and 20 percent were senior administrators. The remaining 7 percent included those identifying as “other,” graduate students, and people who chose not to identify their role.

Nearly 90 percent of respondents reported that the intersection of equity and assessment—for instance, implementing assessment practices that support social justice and DEI efforts—was important or very important. However, less than half (46 percent) of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they had the background, training, and skills to do such work. And only 47 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they had the support needed from their institution to conduct equity-centered assessment.

Regarding types of equity-centered assessments employed, more than 50 percent of respondents engaged in the following: culturally responsive assessment (61 percent), socially just assessment (56 percent), and bias-free assessment (55 percent). Forty-one percent practiced anti-racist assessment. Thirty-eight percent implemented assessment for social justice, and 35 percent performed deconstructed assessment. Just 23 percent of respondents implemented decolonizing assessment. (Read more about these types of assessment here.)

The research team asked respondents about a variety of equity-centered assessment practices that could be used. More than 50 percent of respondents reported that they always or almost always

- ensure demographic questions and categories are up to date and inclusive (67 percent)

- avoid deficit-based or non-inclusive language in reporting (64 percent)

- consider whether demographic categories are inclusive and up to date (61 percent)

- disaggregate data by population demographics (60 percent)

- use data from multiple sources to identify findings or draw conclusions (58 percent)

- use qualitative data collection processes to ensure the voices of all constituents are heard (53 percent)

- use multiple methods to measure student learning (52 percent)

Less than 50 percent always or almost always

- use data to identify barriers to equitable outcomes, which could include analyzing which students fail or withdraw from courses (49 percent)

- include stakeholders, such as students, in developing learning outcomes (46 percent)

- ensure the experiences of individuals from small populations, such as Native Americans, are explored and included in the process (46 percent)

- use data to advocate for structural changes, such as revisions to academic policies (45 percent)

- engage stakeholders in data interpretation (44 percent)

- review learning outcomes for inclusivity (43 percent)

- review standardized measures for inclusivity (38 percent)

- cocreate assessment measures with students (35 percent)

- engage students in mapping outcomes (17 percent)

The survey results suggest that most assessment professionals believe that equity efforts should be integrated into assessment practices. Even though less than half of respondents said that they possessed the background, training, or skills to put equity-centered assessment practices into action, many still reported that they were implementing practices that not only ensure that the higher education assessment process is equitable but that it can be used to further equity on college campuses.

In addition, administrators may wish to use the survey or a version of it to gauge the prevalence of and attitudes toward equity-centered assessment practices at individual institutions. Results could then be compared to the national data to identify ways to improve the individual institution’s equity-centered assessment practices, which might include offering professional development opportunities to help practitioners learn more about such practices. Readministering the survey periodically would help institutions track assessment practices and attitudes over time.

Ultimately, the results from the first-ever survey of equity-centered assessment practices provides valuable information that we believe can help higher education institutions more equitably implement assessment and use assessment to advance equity on campuses.